Welcome to my blog! In the coming months, I will post on objects related to my Contemporary Monuments to the Slave Past project as well as big ideas I need to sort out. For now, it will not be open for comments but feel free to like!

I selected Alison Saar's Swing Low: Harriet Tubman Memorial (2008) as my first blog post because it is such a powerful and compelling image, and I am currently obsessed with Harriet Tubman as a woman and as a historical figure. The first public monument to an African American woman in New York City, the statue is located at Harriet Tubman Square, formed at the intersection of St. Nicholas Avenue and Frederick Douglass Boulevard at West 122nd Street in Harlem.

The contrast between the verdigris patina of her coat and skirt and the slate black patina of her skin are visually striking. With a stoic expression and determined gaze (think Roman portrait bust), Tubman moves forward with the steam of a locomotive. The bottom of her skirt becomes the pilot of a train, sometimes called a cattle catcher, which was the device mounted at the front of a locomotive to deflect obstacles on the track that might derail the train. Embedded in her skirt are portraits of anonymous faces, the passengers of the Underground Railroad, as well as objects carried north by fugitive slaves including cowry shells, medicine bottles, time pieces, shoe souls, and the broken manacles of slavery.

Alison Saar, Swing Low: Harriet Tubman Memorial, dedicated November 13, 2008. 13 feet (H), bronze and Chinese granite. Photo by Renée Ater.

Trailing behind Tubman and attached to a boulder and her skirt are tree roots. These gnarled, intertwined roots represent Tubman's efforts to uproot the system of slavery and the "pulling up of roots by the slaves and all they had to leave behind." Along the base of the sculpture, Saar included bronze quilt blocks: traditional geometric quilt designs as well as applique blocks of scenes from Tubman's rescue efforts to the Eastern Shore of Maryland.

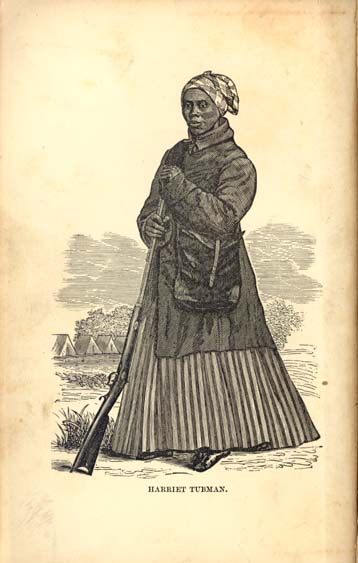

Frontispiece from Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman, ca. 1868. National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, DC.

I think that Saar 's conception of Tubman is based on the 1869 frontispiece from Sarah Bradford’s Scenes in the Life of Harriet Tubman. In June 1863, Tubman became the first woman to lead an armed military raid when she guided Col. James Montgomery and his 2nd South Carolina black regiment up the Combahee River, routing Confederate outposts, liberating more than 700 slaves, and destroying stockpiles of cotton, food, and weapons. Saar incorporated the core visual elements of the nineteenth-century wood engraving including the head wrap, the pleated skirt, and the Union army issued sack coat and haversack. Strikingly, Saar omitted the 1861 Springfield rifled musket. I speculate that Saar and city planners chose deliberately to omit the weapon because of the location of the memorial across from the 28th Precinct of the NYPD, and its long and difficult history of policing the once predominantly black Harlem. What would it have meant to have a statue of an armed black women in such a prominent public space?