On Friday morning, September 27, I continued my trip from Albany to Troy and Schenectady. I was particularly interested in seeing the recently installed William Seward and Harriet Tubman Statue, Historic Vale Cemetery, and the African-African Ancestral Burial Ground within the cemetery. Later in the afternoon, I headed to Kingston, Ontario. From Kingston, I drove the perimeter of Lake Ontario on the Canada side, arriving in St. Catharines on Sunday late afternoon (Toronto, you hands down win the award for the worst traffic. Wow. You make Interstate 10/405 in Los Angeles look like baby’s play!)

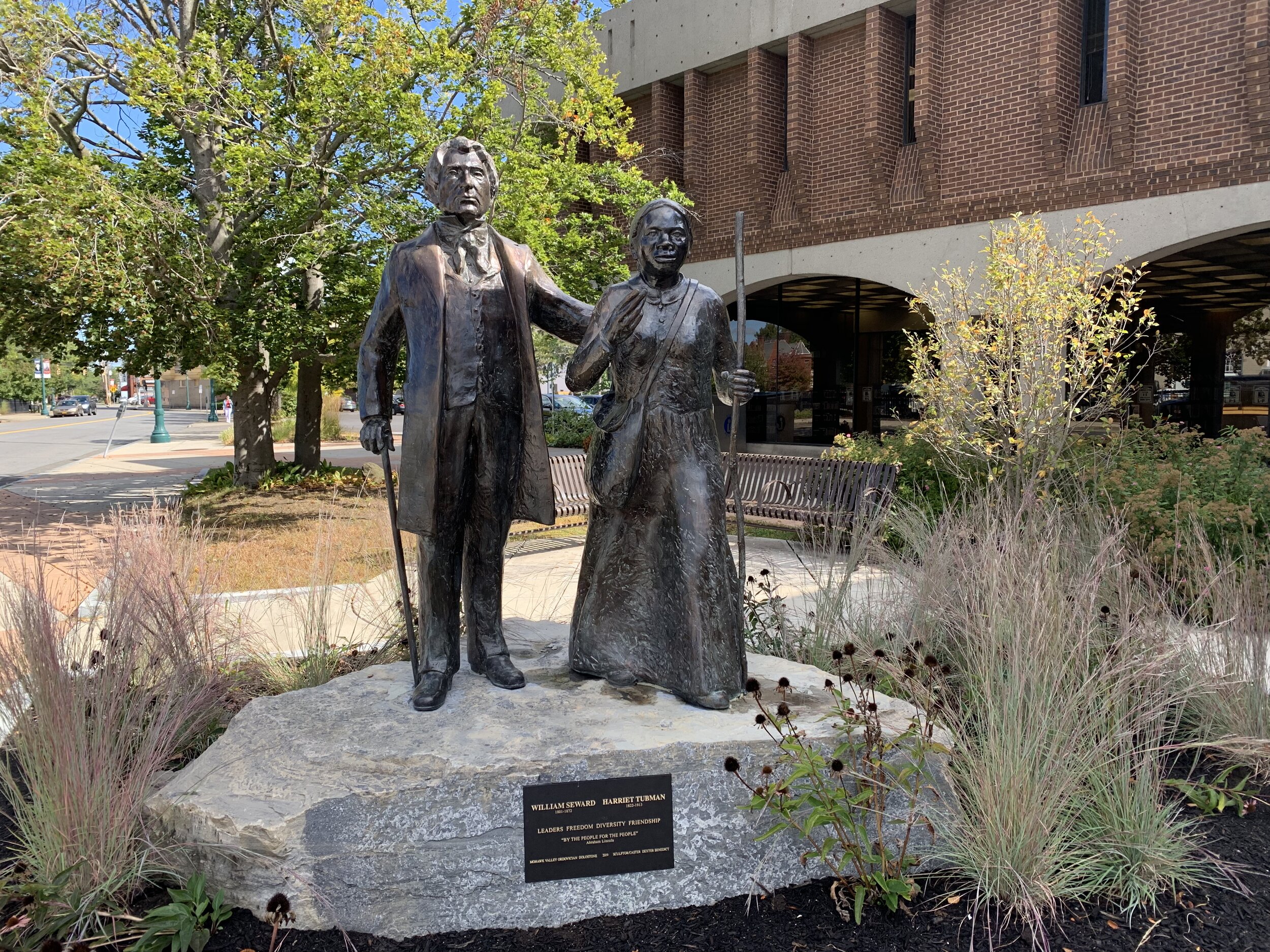

City officials dedicated the William Seward and Harriet Tubman Statue on May 17, 2019, at the corner of Clinton and Liberty Streets in downtown Schenectady. Frank Wicks, an emeritus mechanical engineering professor at Union College, initiated the fundraising efforts to create the monument. Local artist, Dexter Benedict, was commissioned to create the life-size figures in bronze standing on Mohawk Valley dolostone surrounded by native plants.

The monument honors the friendship between the two. Seward (1801-1872) was a New York State Senator, Governor of New York, a United States Senator, and served as Secretary of State under both the Abraham Lincoln and Andrew Johnson administrations. He is credited with spearheading the purchase of the Alaskan Territory from Russia in 1867. Tubman (1822-1913) is best known for her role as a conductor on the Underground Railroad; she made thirteen trips to the Eastern Shore of Maryland and brought approximately seventy people (family and friends) to freedom in St. Catharines, Canada West (Ontario). During the American Civil War, Tubman served as a Union spy, scout, and nurse. After the war, she played an important role fighting for black equality and women’s suffrage.

Both Tubman and Seward had ties to Schenectady. Tubman is known to have come through Schenectady after the famed Charles Nalle Rescue in Troy. Seward attended Union College and graduated from the school in 1820. Besides this connection to Schenectady, Tubman and the Sewards had a relationship based in their mutual fight against slavery. During the 1850s, Seward’s home in Auburn, NY, served as an important stop on the Underground Railroad with Seward’s wife, Frances (1839-1865), actively engaged in the abolitionist network and hid freedom seekers in her basement. In 1859, Tubman purchased a seven acre farmstead in Auburn from the Sewards, where she was based until her death in 1913. The relationship between them lasted until Frances’s and then William’s death. During the Civil War, Frances provided shelter to Tubman’s niece (speculation that she might have been Tubman’s daughter), Margaret Stewart. Immediately after the war, William advocated that Tubman should receive a government pension for her service as a scout and nurse in the U.S. Army.

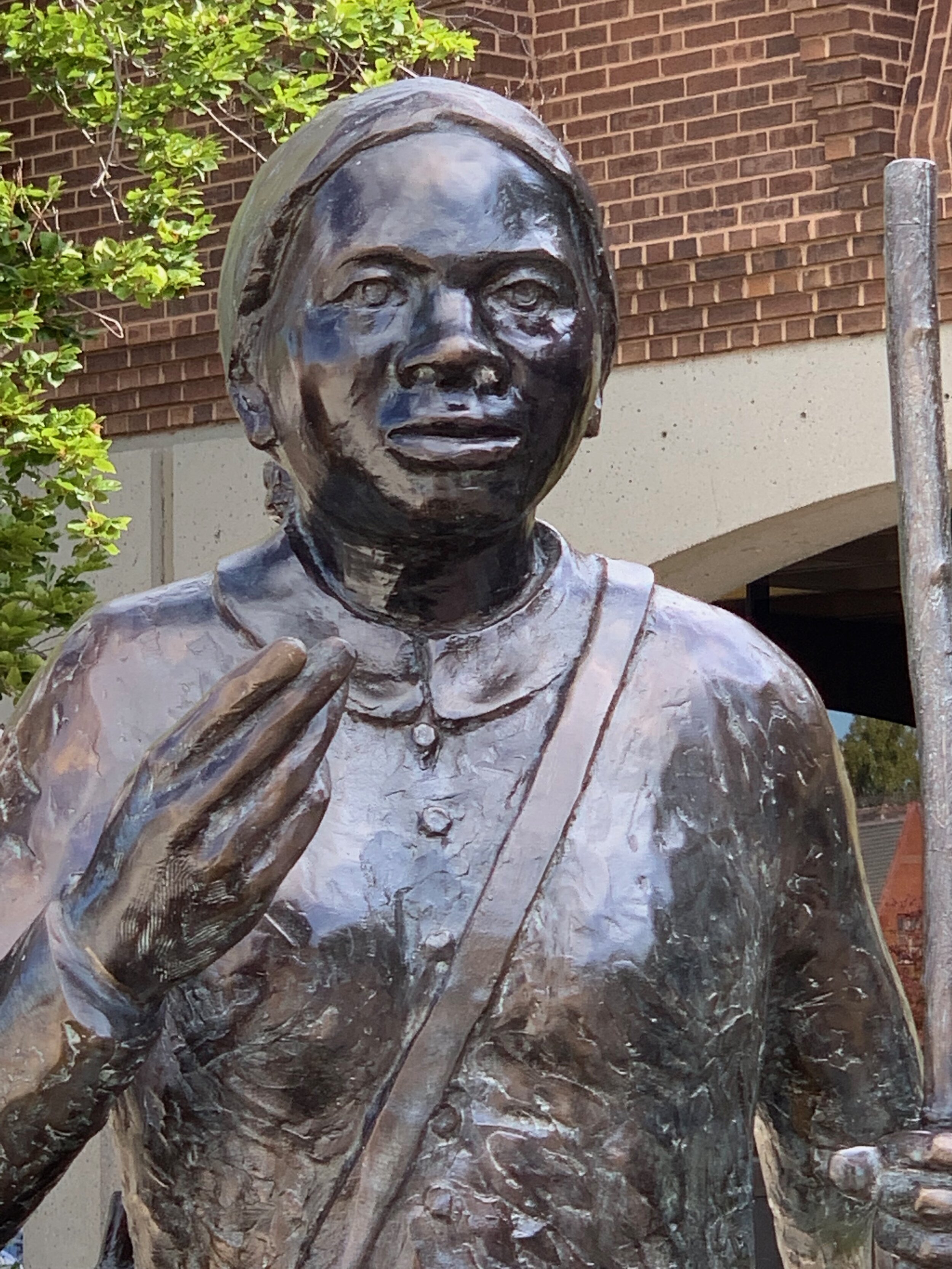

Placed in front of the Schenectady County Public Library, the statue shows Seward and Tubman striding forward with Seward holding a cane and Tubman carrying a long walking stick. Both are dressed in nineteenth-century clothing, with their faces and poses based on historic photographs. Perhaps the oddest element of the statue is the embrace. Seward reaches his left arm around Tubman’s bronze back but does not touch her. Depicted with her right hand gesticulating upward, Tubman appears to be striding away from Seward. Although not intended by the artist nor those who commissioned the statue, I can’t help but read the gesture as one of paternalism: the white male savior guiding the black woman along the correct path. I’ll have to think about this more deeply but for now I see an incongruity between the statesman and the diminutive freedom fighter.

While I was standing in front of the monument, an African American couple in their early twenties came by to take photos. The young man pointed out the revolver to me and delivered an accurate history of Tubman’s work on the Underground Railroad. I say accurate because I often meet people at monuments who tell me fantastical things about them. The young man told me her gun made her “radical.” Indeed, it did. For visitors to the statue, it is a reminder that Tubman was tough. Its presence reminds us that she carried a fire arm to protect those she led to freedom and in her role as a scout during the Civil War.

For a discussion about the William Seward and Harriet Tubman Statue and the dedication ceremony, select the video below: “Wade in the Water: Unveiling of the Harriet Tubman - William Seward Statue.”