The final stop on my travels along the NY State Network to Freedom was a return to Auburn to visit the Harriet Tubman Commemorative Statue and the newly opened New York State Equal Rights Heritage Center. Created by Brian Hanlon, the seven-and-half foot tall (2.3 meters) bronze statue represents a young Harriet Tubman, traveling on the Underground Railroad. Clothed in nineteenth-century shawl, jacket, and pleated skirt, Tubman strides forward with her booted foot visible below the hem of her skirt. She extends her left hand behind her as if signaling to an invisible group to follow closely on the arduous route to Canada. In her right hand, she holds the ring of a lantern, illuminating the pathway to freedom.

Brian Hanlon, Harriet Tubman Commemorative Statue, 2019, Equal Rights Heritage Center, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

The larger-than-life size statue forms a weighty pyramid, with Tubman’s wide skirt anchoring the composition. Her arms break the horizontal plane of the polyhedron. Given Tubman’s significance to Auburn, she lived on a farm in the town and is buried in Fort Hill Cemetery, a commemorative statue to her makes sense. The monument does what it is supposed to do: it emphasizes her corporeal presence in the landscape, and it points to the area’s rich connection to the Underground Railroad and the fight for freedom and equal rights.

Brian Hanlon, Harriet Tubman Commemorative Statue, 2019, Equal Rights Heritage Center, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

Upon encountering the statue, I was immediately struck by the youthfulness of Tubman’s portrait—in many public monuments she is depicted as an older woman. Hanlon has said that he aspired to portray Tubman’s “strength and courage as a young warrior.” The sculptor modeled Tubman with a broad forehead, almond shaped eyes with carved pupils, a wide nose, and full lips. Tubman wears short natural hair, wrapped in a piece of cloth. Her expression and posture conveys her strength of character and body (despite her small stature and disabled body).

Similar to the other statues that I saw on my trip across Central New York, Hanlon utilizes figuration rooted in the classical past. Over and over again, I am finding that communities prefer (or perhaps negotiate) representation over abstraction, and the visually accessible over the conceptual. They want realism and the weight of bronze with the assurance of the statue’s legibility and longevity for future generations.

Brian Hanlon, Detail of lantern from Harriet Tubman Commemorative Statue, 2019, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

Brian Hanlon, Detail of haversack and pistol from Harriet Tubman Commemorative Statue, 2019, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

Three details on the monument narrate the monument. The lantern in Tubman’s right hand shines the way for freedom seekers and is also used as the logo for the Equal Rights Heritage Center, suggesting that the light of liberty and justice will always shine from New York State. On her left shoulder, Tubman carries a haversack that is tightly belted. Widely used during the American Civil War, the haversack reminds me of Tubman’s service as a nurse and scout during the war. Behind the haversack and tucked into the belt of her jacket is the butt of a revolver. Tubman’s biographer, Sarah H. Bradford, described that Tubman carried the revolver to encourage freedom seekers to keep moving forward.

“By night she traveled, many times on foot, over mountains, through forests, across rivers, mid perils by land, perils by water, perils from enemies, ‘perils among false brethren.’ Sometimes members of her party would become exhausted, foot-sore, and bleeding, and declare they could not go on, they must stay where they dropped down, and die; others would think a voluntary return to slavery better than being overtaken and taken back, and would insist upon returning; then there was no remedy but force.”

Equal Rights Heritage Center, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

The statue of Harriet Tubman is placed across the plaza, slightly removed from the main entrance of the Equal Rights Heritage Center. The statue and the Center are co-dependent, meaning that the two are interconnected and emphasize the idea of hard earned freedom and equal rights. Upon arriving at the Center, I have to admit that had no idea of its purpose. I anticipated a museum dedicated to Tubman, and the history of Auburn and abolitionism.

Entrance with introductory text panel, Equal Rights Heritage Center, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

Entrance with lantern logo, Equal Rights Heritage Center, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

What I found at the Equal Rights Heritage Center was something totally different: a expansive visitor center with interactive maps and videos, the “Seeing Equal Rights in New York State” exhibit, as well as a Taste NY Market, where visitors can purchase state-produced items.

The exhibition text panel above the visitor information desk reads:

“New Yorkers have always led the way. In New York State, we’re proud to embrace our differences. We are all New Yorkers, and we are strong because we are diverse. Whether we’ve been here one day or our whole lives, we all belong. Our voices matter here, our rights our protected, and our differences are celebrated. In our storied history in the fight for the abolition of slavery and our important role in the Underground Railroad, to the start of the women’s right movement, to the birth of the modern LGBTQ rights movement, New Yorkers have always been at the forefront of the fight for a more inclusive world. Within this “Seeing Equal Rights in New York State” exhibition you will find inspiration and strength in the leadership New Yorkers have played in furthering freedom. We invite your to explore the people and places of New York that have made an impact on the continuous pursuit of equal rights within this exhibition, and across our great state.”

At its core, the center is about promoting tourism for Central New York, with a stress on the state’s progressive history in relation to women’s rights, abolitionism, civil rights, and LGBQT rights. It is not a traditional museum but rather a place to gather information in order to travel to other historic sites, parks, and museums.

Click on the image above to activate the slide show.

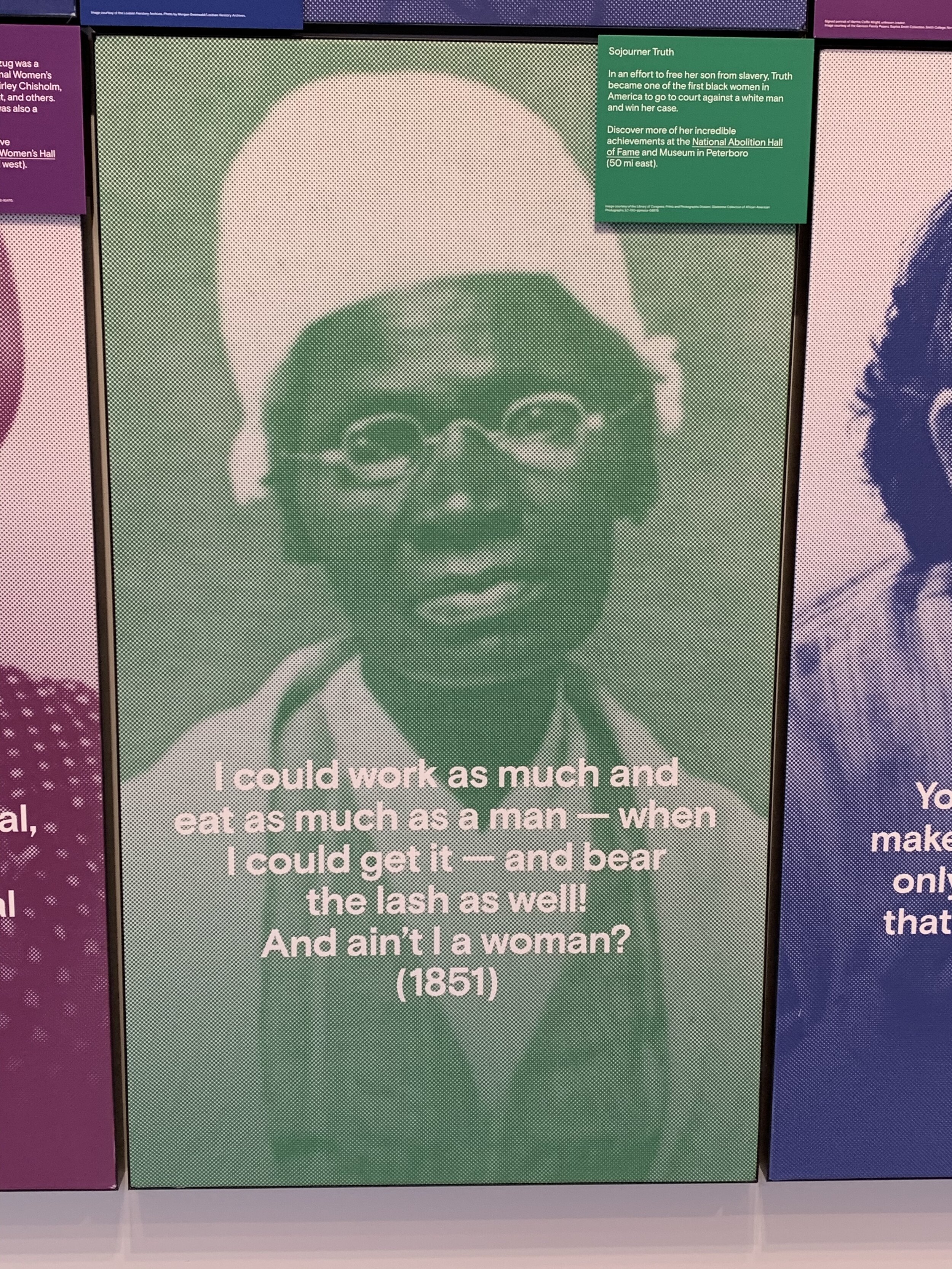

On several of the walls, visitors encounter rows of portraits of diverse women and men of New York who fought locally and nationally for equal rights, including images of nineteenth-century abolitionists Harriet Tubman, William Seward, Garret Smith, Frederick Douglass, and Sojourner Truth. All portraits include quotations.

Social Justice Table, Equal Rights Heritage Center, Auburn New York. Photographs by ©James Ewing/OTTO, see nARCHITECTS, http://narchitects.com/work/heritage-center/.

I stopped briefly at the Social Justice Table — a round table with tablets that contain history of the various equal rights sites. The Center also includes an immersive map video that highlights different types of “attractions” across the state including historic homes, Underground railroad sites, and interpretive centers.

Broadsides, Banners, Handbills, and Posters Exhibit, Equal Rights Heritage Center, Auburn, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, October 2019.

Along with the Social Justice Table and the video map, the Center includes several montages of reproduced posters, broadsides, banners, and handbills. These images range from a broadside announcing an anti-slavery mass meeting, a poster trumpeting “Votes For Women 1915,” a broadside heralding a “Malcolm X Commemoration Day”, and an AIDS poster declaring “Silence = Death.” I thought these the most effective visual elements of the exhibition.

At the end of my circuit through the Center, I was left thinking about equal rights and cultural heritage as tourism and about New York State boosterism. As seen in the exhibit, videos, and interactive map, New York is deemed a historic progressive state with progressive citizens. The narratives at the Center leave no room for the difficult and contentious aspects of the state’s history, including slavery. Feeling slightly disappointed, I left the Center and crossed over the plaza to take a tour of the Seward House Museum.

Click on the image above to activate the slide show with images of the Seward House Museum and the “Forged in Freedom” exhibition.

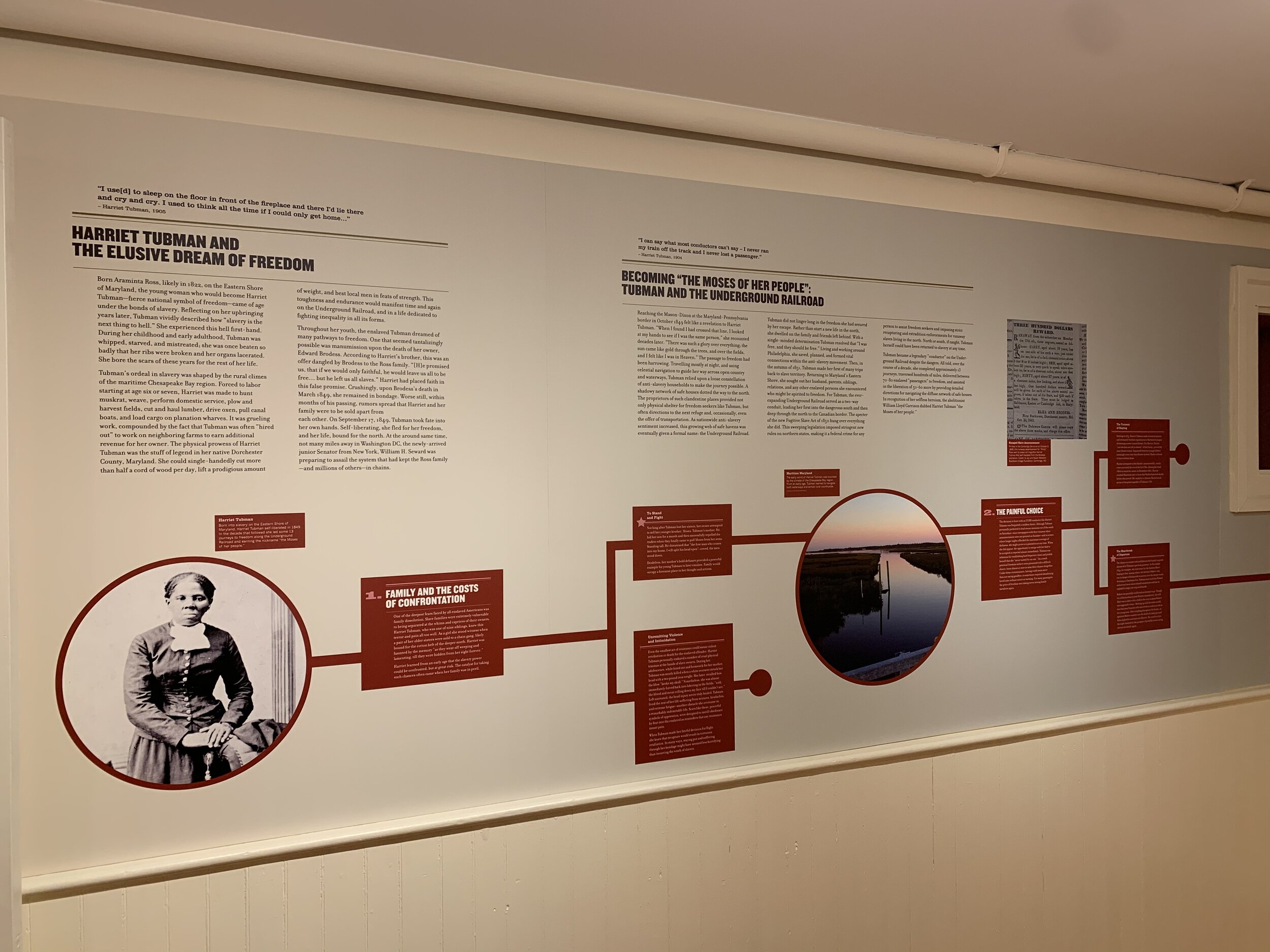

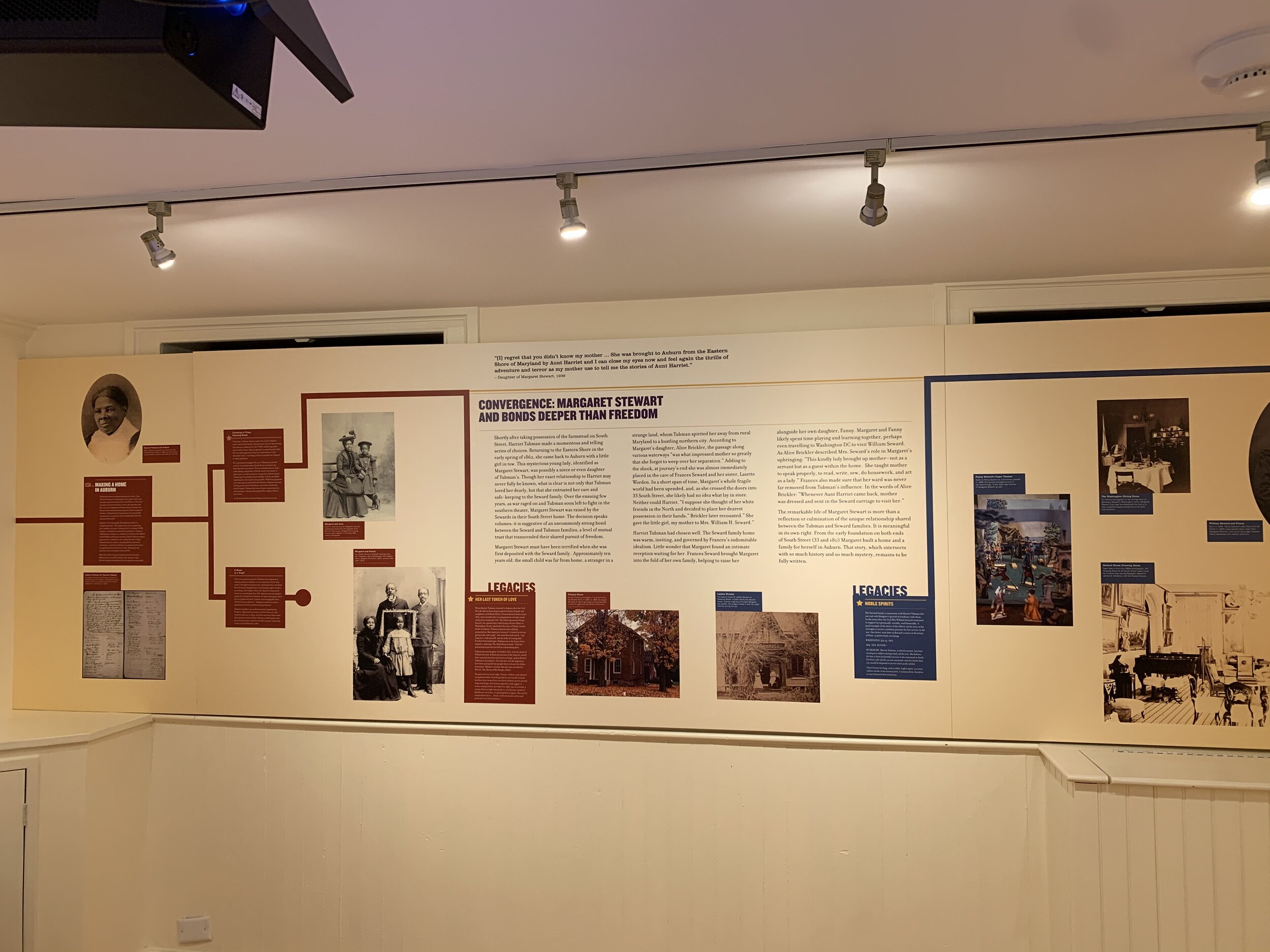

A graduate student in history gave a small group of us a thoughtful, historical tour. Rather than a discussion of objects, he built a context for the Sewards’ lives over time. In the basement of the house, “Forged in Freedom: The Bond of the Seward Tubman Families” is an excellent exhibition about the relationship between Harriet Tubman and the Sewards. The mansion was a safehouse on the Underground Railroad. Stationmaster Frances Adeline Miller Seward, William Seward’s wife, hid freedom seekers in the basement kitchen. Together, the house tour and the exhibition delivered a nuanced story of two families engaged in personal relationships and their mutual fight against slavery.