After visiting the William Seward and Harriet Tubman Statue in downtown Schenectady, I drove less than a mile south to Historic Vale Cemetery.

Upon entering the cemetery from State Street, I encountered a peaceful picturesque park filled with trees and winding pathways. I took a few minutes to take in the quiet contemplative space.

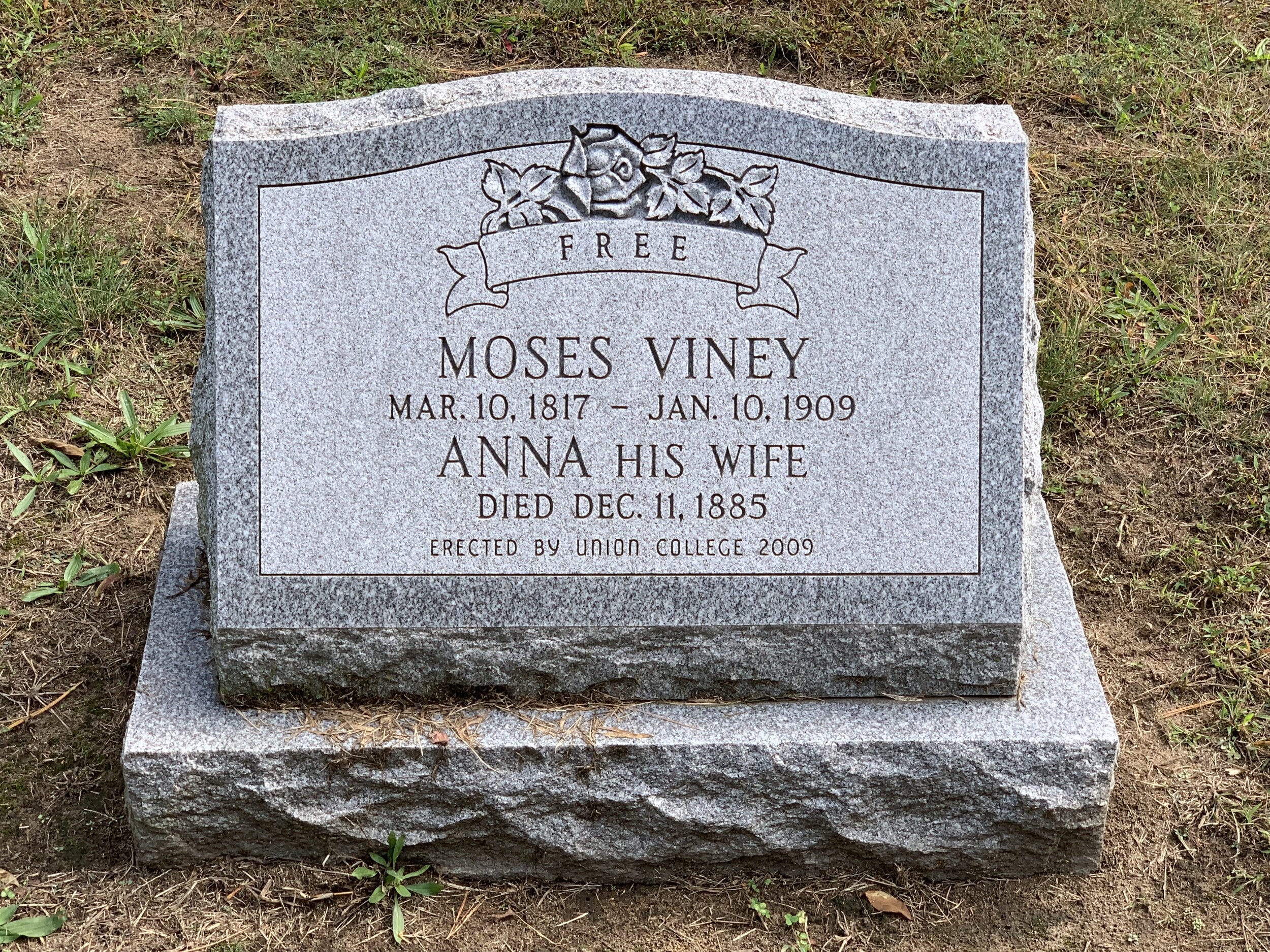

With no sense of where I was headed, I drove down the main street of the cemetery in search of the African-American Ancestral Burial Ground. In particular I was looking for the headstone of Moses Viney (1817-1909) , who escaped from slavery on the Eastern Shore of Maryland to Schenectady on the Underground Railroad in April 1840. Viney then found employment with then-Union College president, Eliphalet Nott (1773-1866), as a coachman, messenger, and caretaker. Union College erected a headstone to Viney in 2009.

Click on the image below to activate the slide show.

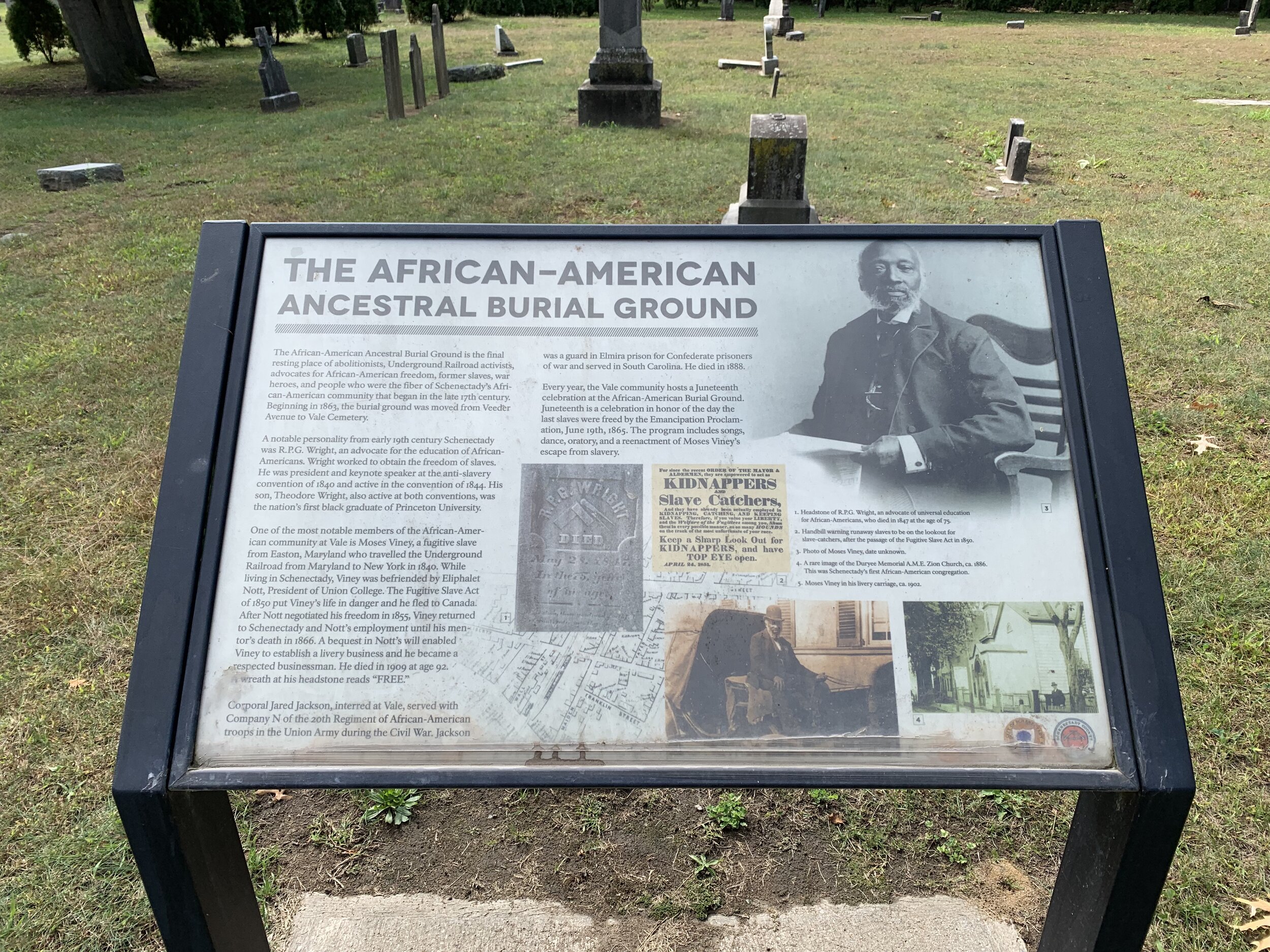

With dumb luck and a left turn, I quickly found the African-American Ancestral Burial Ground and Viney’s gravesite. The information panel states that the burial ground is the “final resting place for abolitionists, Underground Railroad activist, advocates for African-American freedom, former slaves, war heroes, and people who were the fiber of Schenectady’s African-American community.” Originally located along Veeder Avenue and known as the “Colored Cemetery,” the burial ground was moved sometime between 1861 to 1863, with bodies exhumed and reburied in the new “Colored Plot” at Vale Cemetery.

Three men are singled out on the text panel: Viney, Richard P. G. Wright (ca. 1772-1847), and Corporal Jared Jackson (1840-1888). Wright, a barber by trade, was an abolitionist, an early member of the American Anti-Slavery Society, a founding member of the Anti-Slavery Society of the City of Schenectady, and active in the New York Committee of Vigilance. His headstone bears a Freemason square and compass; he and his son Theodore Sedwick Wright were the only African American members of the St. George’s Masonic Lodge in Schenectady. Viney’s grave is marked with a contemporary headstone embedded with a carved rose and the words “FREE” etched on a banner below the roses. Jackson served with Company N of the New York 20th Regiment of the United States Colored Troops. I could not locate Jackson’s headstone.

One of the most interesting headstones marked Jacob Robinson’s grave. Born around 1837, Robinson died in 1898 a member of the Grand United Order of Odd Fellows. Atop his headstone rests three linked circles, the official “logo” of the Odd Fellows, representing the ideals of friendship, love, and truth

As I moved further back into the burial ground, I realized something was amiss. I discovered that six headstones had been vandalized, pushed completely off their bases. Behind a screen of arbor vitae, to the right of the trees in the picture below, beer cans lay discarded on the ground.

Feeling dismayed at this desecration, I took a moment to breathe. The damaged graves include the following:

✪ Reverend Albert Johnson, 1852-1926, Troop K, New York 10th Regiment, U.S. Cavalry. At Rest.

✪ William Childers, Company F, New York 26th Regiment, United States Colored Troops, Died August, 25, 1890, Aged 49 Years.

✪ Mother, Anna Dunbar, 1858-1924

✪ Gertrude Elizabeth, daughter of Charlotte Wilson, July 9, 1907 - April 11, 1924

✪ Schuyler Fraser, 1870-1929

Click on the image below to activate the slide show.

In recent years, several journalists have written about the demise of historic black cemeteries and the lack of funding to preserve them including Dawn Olney, Jerrel Floyd, Brian Palmer, and Seth Freed Wessler. In February 2019, Representative Alma S. Adams (D-NC) and Representative A. Donald McEachin (D-VA) introduced H.R. 1179, which would establish within the National Park Service the African-American Burial Grounds Network. The goal is to document, preserve, and intepret historic African American cemeteries. The NPS has pushed back against the act, citing a lack of resources: “locating and protecting these sites while also developing the Network in all the ways the bill describes would be incredibly challenging and costly.”

I simply note that to do this kind of damage in a historically designated African American cemetery, takes a hate-filled heart and a deep disrespect for the African Americans buried in this place.