“We have seen the Mere Distinction of Colour made in the most enlightened period of time, a ground of the most oppressive dominion ever exercised by man over man.”

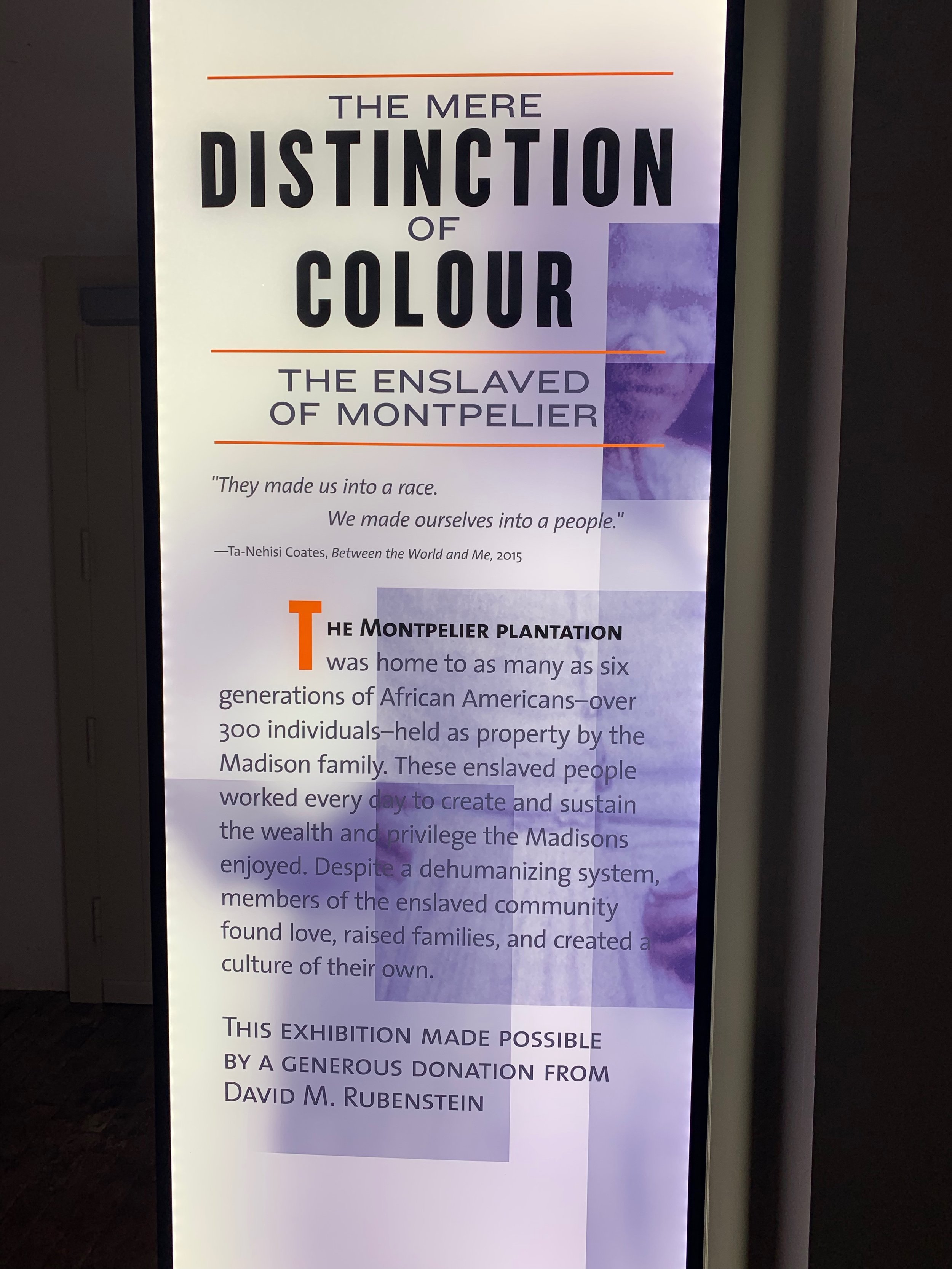

James Madison wrote these words in 1787, acknowledging that phenotype had allowed men of European descent to enslave Africans in an economic regime of subjugation and terror. This quotation is the fulcrum of the interactive exhibition “The Mere Distinction of Colour.”

Brick mosaic of young enslaved boy constructed out of brick pieces excavated from the South Yard. Some of the shards contained fingerprints of the brick makers. Created by Proun Design, The Montpelier Foundation. Photo by Renée Ater, August 2019.

Archaeology is an important tool for retrieving “the hidden lives” of those enslaved at Montpelier, according to Kat Imhoff, President and CEO of the Montpelier Foundation. Montpelier received a four-year grant (2010-2014) from the National Endowment of the Humanities to excavate, analyze, and interpret slave housing at Montpelier. Much of the interpretation in this exhibition is tied to this archaeological work.

Select the video below to watch the story of the excavations of the slave quarters at Montpelier.

Archaeology and Slavery: Slave Quarters Excavation at James Madison’s Montpelier. NEHgov, published October 21, 2013.

The interactive exhibition is located in the South Yard (see blog post: Slavery and Montpelier, Part I) and the South and North Cellars of James and Dolly Madison’s home. The cellars were used for storage and acted as an important social space called a “servants hall.” Emotionally powerful, the exhibition traces two narrative arcs in the cellars: “The Montpelier Story of Slavery as Told by Living Descendants” and “The National Story of Slavery & the Economic Impact of the Institution.” We entered through the South Cellar, and encountered whitewashed walls with the names of slaves stenciled on the wall at chest level. This unsettling site of the names running around the course of the room—particularly the stenciled “Name Unknown”—provoked me to think of the countless times these men and women entered these spaces to serve the Madisons, yet they were not acknowledged or recorded as existing in any significant way.

Names listed on wall in South Cellar, Montpelier. Photo by Renée Ater, August 2019.

The South Cellar focuses intently on the lives of the slaves at Montpelier. With clear and thoughtful language, all of the exhibition texts reminds visitors of the humanity of individuals. Yet, much of this content is not cogently translated into the house, where there is a mention of Paul Jennings, but no indication that slave labor constructed the house and that such labor was necessary for the day-to-day functioning of the house. Nothing functioned at Montpelier without slave labor. In fact, some visitors could avoid the issue of slavery at Montpelier completely by solely attending the “Signature Tour” or the “Madison and the Constitution Tour.” In the South Cellar, I observed one older white couple read the introductory label then exit quickly. I was reminded of the July Twitter storm and subsequent press coverage about a white woman who conveyed her extreme disappointment that the tour of a Louisiana plantation included a discussion of slavery. Some want narratives that avoid the harsh realities of chattel slavery, and stories that ignore slavery’s intertwined role in the founding of the nation. Montpelier would like visitors to wrestle with this legacy in real ways.

Click on the image below to activate the slide show.

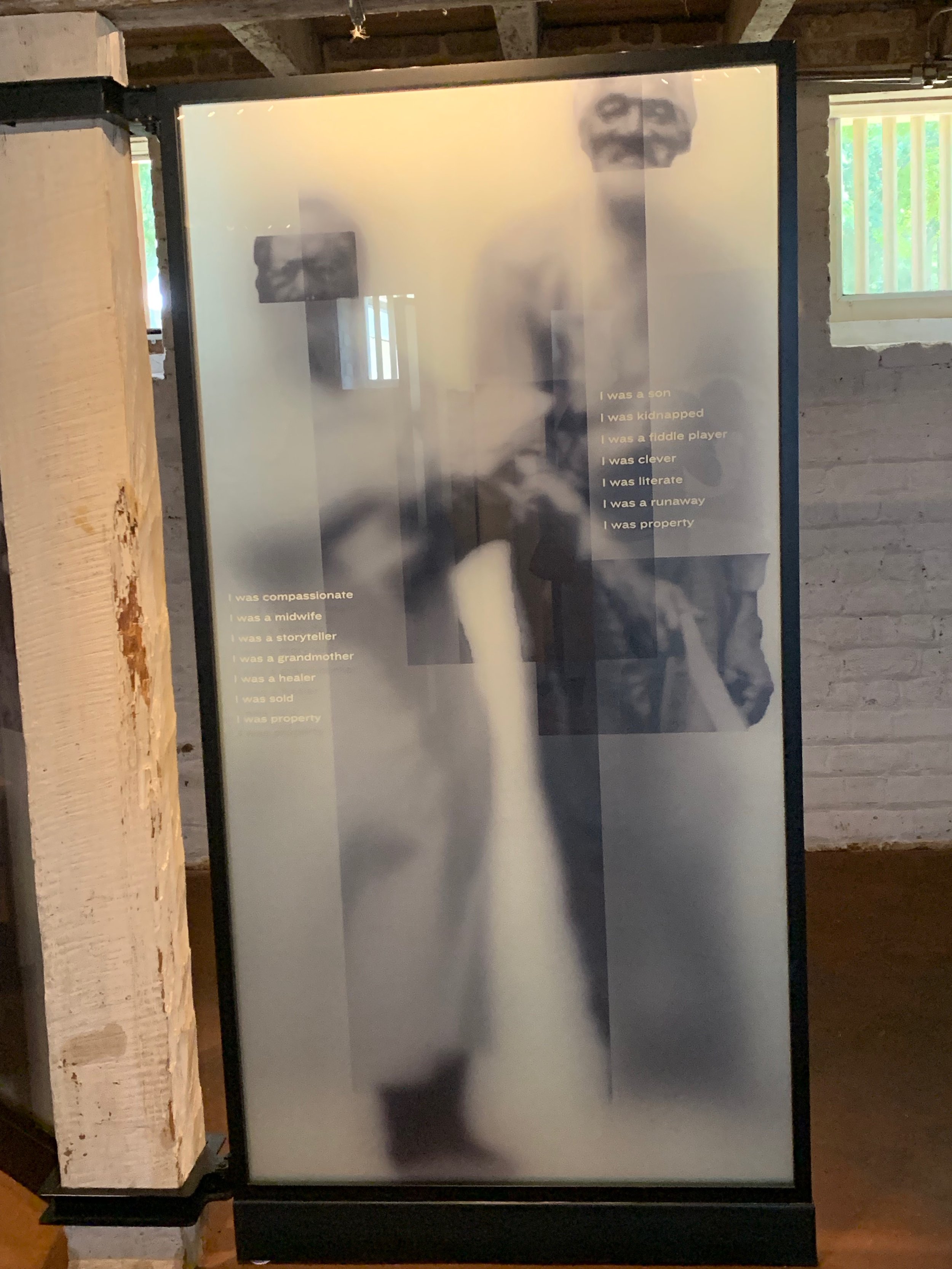

The declarative sentences on large hanging text panels assert the subjective life of enslaved persons. A particularly moving example framed the experience of a female slave:

I was a wife

I was separated

I was raped

I was afraid

I was hopeful

I was a survivor

I was property.

Although I came away with the notion of Madison as a “benevolent” slave owner after the house tour, these simple declarative sentences reminded me that there is zero benevolence in chattel slavery. These statements are part of a narrative in the South Cellar that points to the ugliness of slavery and the beauty of human resistance.

“Person or Property,” from The Mere Distinction of Colour exhibition, Montpelier. Photo by Renée Ater, August 2019.

In the final section of the South Cellar, visitors encounter a evocative video installation, “Fate in the Balance,” projected on the blank white washed walls of the cellar. Northern Light Productions, the makers of the film, used charcoal illustrated animation to tell the story of Ellen Stewart, who was born into slavery at Montpelier, and witnessed the separation of her family. It is a powerful tale of the destructive nature of slavery. As I watched the film, I found myself experiencing a range of emotions from sadness to horror to anger. The evocative use of charcoal haunts the South Cellar wall, the ghosts of the past ever present, their stories waiting to be told and retold.

Select the video below to watch a short segment of “Fate in the Balance.”

The North Cellar contains the story of slavery writ large, “The National Story of Slavery & the Economic Impact of the Institution.” This story is told through the idea of “America’s contradiction,” rather than moral or ethical hypocrisy. With detailed interactive panels, we learn of the economics of slavery, slavery and the American presidency, Madison’s opinions about and actions in regard to slavery, and slavery in the Constitution. I was impressed with the comprehensive yet straightforward texts panels. One of the most striking videos in the North Cellar exhibit uses an interactive map to show the growth of the domestic slave trade from the three top slave-selling states: Virginia, South Carolina, and Maryland. After the United States officially abolished the transatlantic slave trade in 1807, plantation owners sought new ways to sell and make profit off human beings. In measurable form, the interactive map details the movement of slaves to the Deep South; between 1824-1834, slave owners had sold nearly 300,000 slaves in the domestic slave trade, 25% of them children. This simple map with each dot representing a 1,000 people is a stunning visualization of the growth slavery in the United States.

Select the link to the interactive map or go directly to Proun Design for access to video.

“Slavery in the Constitution,” from The Mere Distinction of Colour exhibition, Montpelier. Photo by Renée Ater, August 2019.

The North Cellar exhibition ends on a powerful note with Northern Lights Production’s five-screen video, “Legacies of Slavery.” The film follows the impact of slavery on American society, tracing an arc from convict leasing to the Civil Rights Movement to contemporary police brutality and the rise the Black Lives Matter movement. At the beginning of the film, I was struck by one commentator’s remarks about our resistance to the messiness of history: “What we love is nostalgia. We love to remember things exactly the way they didn’t happen. And history itself is often an indictment.”

Select the video above to watch Chris Denemayer of Proun Design discuss his exhibition design “The Mere Distinction of Colour.”