Rochester was my next stop on the New York State Network to Freedom to see the Frederick Douglass Monument (1899). A typical example of Beaux-Arts portrait sculpture in bronze, the eight-foot tall (2.4 meters) statue rests atop a nine-foot tall (2.7 meters) Westerly blue granite base. It is thought to be the first public monument to an African American in the United States.

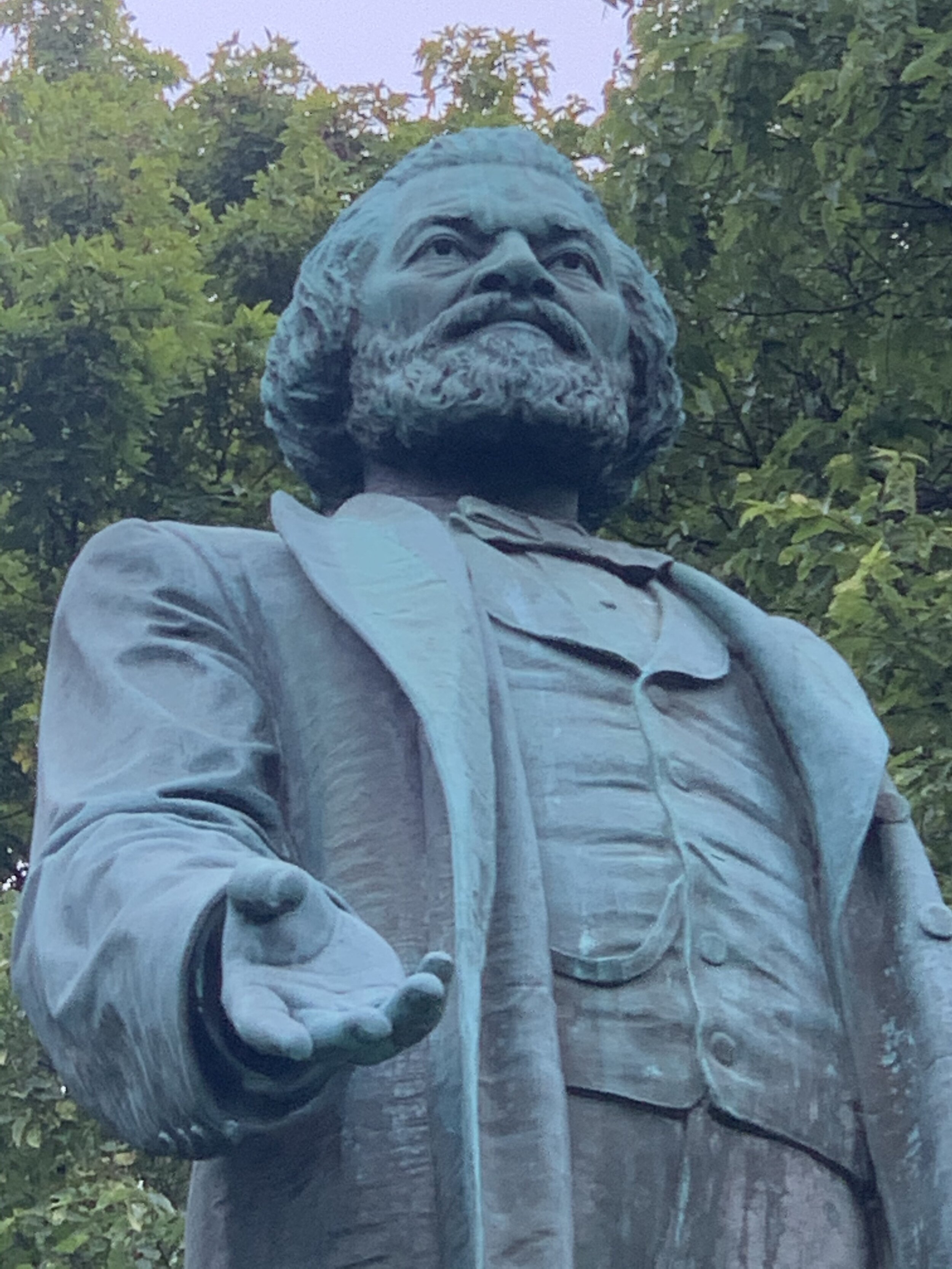

Stanley W. Edwards, Frederick Douglass Monument, 1899, Highland Park Bowl, Rochester, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, September 2019.

Four bronze plaques adorn the pedestal, inscribed with Douglass’ words. Facing the monument to the south, the first plaque is marked in bronze capitalized lettering with the freedom fighter’s name: “Frederick Douglass.”

Moving counter clockwise, the east side of the plinth reads: “I know no soil better adapted to the growth of reform than American soil. I know of no country, where the conditions for effecting great changes in the settled order of things, for the development of right ideas of liberty and humanity are more favorable than here in these United States.” Extract from speech on Dred Scott Decision, delivered in New York, May 1857.

The north facing plaque is lettered with three quotes: “The best defense of free American institutions is the hearts of the American people themselves”; “One with God is a majority”; and “I know no rights of race superior to the rights of humanity.”

The east side of the plinth contains these words: “Men do not live by bread alone; so with nations, they are not saved by art, but by honesty; not by the gilded splendors of wealth, but by the hidden treasures of manly virtue; not by the multitudinous gratification of the flesh, but by the celestial guidance of the spirit.” Extract from speech on The West India Emancipation, delivered at Canandaigua, N.Y., August 4, 1857.”

Click on the image below to activate the slide show to view the four bronze plaques with Douglass’ words.

At the time of my visit on September 30, 2019, the Frederick Douglass Monument was located in Highland Park Bowl, above the park’s amphitheater, obscured by a grove of trees and hard to find. Originally, the statue was positioned in front of the old New York Central Train Station in downtown Rochester. It was moved to Highland Park in 1941 to be closer to where Douglass’ hillside farm stood on South Avenue. As of December 4, 2019, the city of Rochester relocated the monument to the newly created Frederick Douglass Memorial Plaza at the corner of South Avenue and Robinson Drive, a more prominent and accessible section of the park.

Stanley W. Edwards, Frederick Douglass Monument, 1899, Highland Park Bowl, Rochester, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, September 2019.

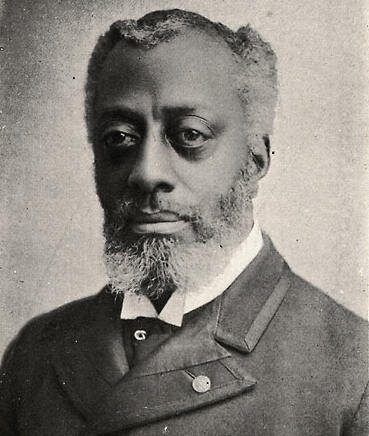

Originally intended to be carved in granite, Stanley W. Edwards created the statue that was ultimately cast in bronze. Edwards studied with the Danish-born Edward Ludwig Albert Pausch (1856-1931) in Buffalo, New York, and is best known for his granite Civil War memorials at Antietam National Battlefield in Sharpsburg, Maryland. At the time of the creation of the statue, he worked for the Smith Granite Company in Westerly, Rhode Island. Edwards used Frederick Douglass’s youngest son, Charles Redmond Douglass (1844-1920), as the model for the dignified portrait.

Below is a detail of the monument, and to the right, a photograph of Charles Edmond Douglass.

The solemnity of the imposing bronze figure of Douglass struck me immediately. The abolitionist and radical defender of liberty is shown with extended hand, engaged in oration. In one of the most important early books on American sculpture, Freeman Henry Morris Murray (Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture, 1916) wrote the following words about the Douglass statue:

“The pose is dignified and commanding. It is intended to portray the attitude of the distinguished orator as he stood before a large concourse of people in Cincinnati and made his first public address after the final ratification of the Fifteenth Amendment. We can well imagine that we hear him saying in a tone of sober triumph: ‘Fellow Citizens: I appear before you tonight for the first time in the more elevated position of an American citizen.’ Those who knew Douglass well will appreciate the strength of this work. It is not merely a man with such and such physical features, it is markedly personal, and clearly represents a person of more than ordinary force and commanding presence (107-108).”

“Exhibit on American Negroes at the Paris Exposition,” 1900, Library of Congress, Washington, DC. Illustration in: The American Monthly Review of Reviews, vol. XXII, no. 130 (1900 November), p. 576.

Interestingly enough, I first encountered the sculpture as a reproduction through the above photograph while I was researching my dissertation on Meta Warrick Fuller (1877-1968). W. E. B Du Bois included the statuette in his famous “Exhibit on American Negroes” for the Paris Exposition of 1900. Du Bois placed the statuette on a shelf, seen on the left in the photograph above the low bookcases.

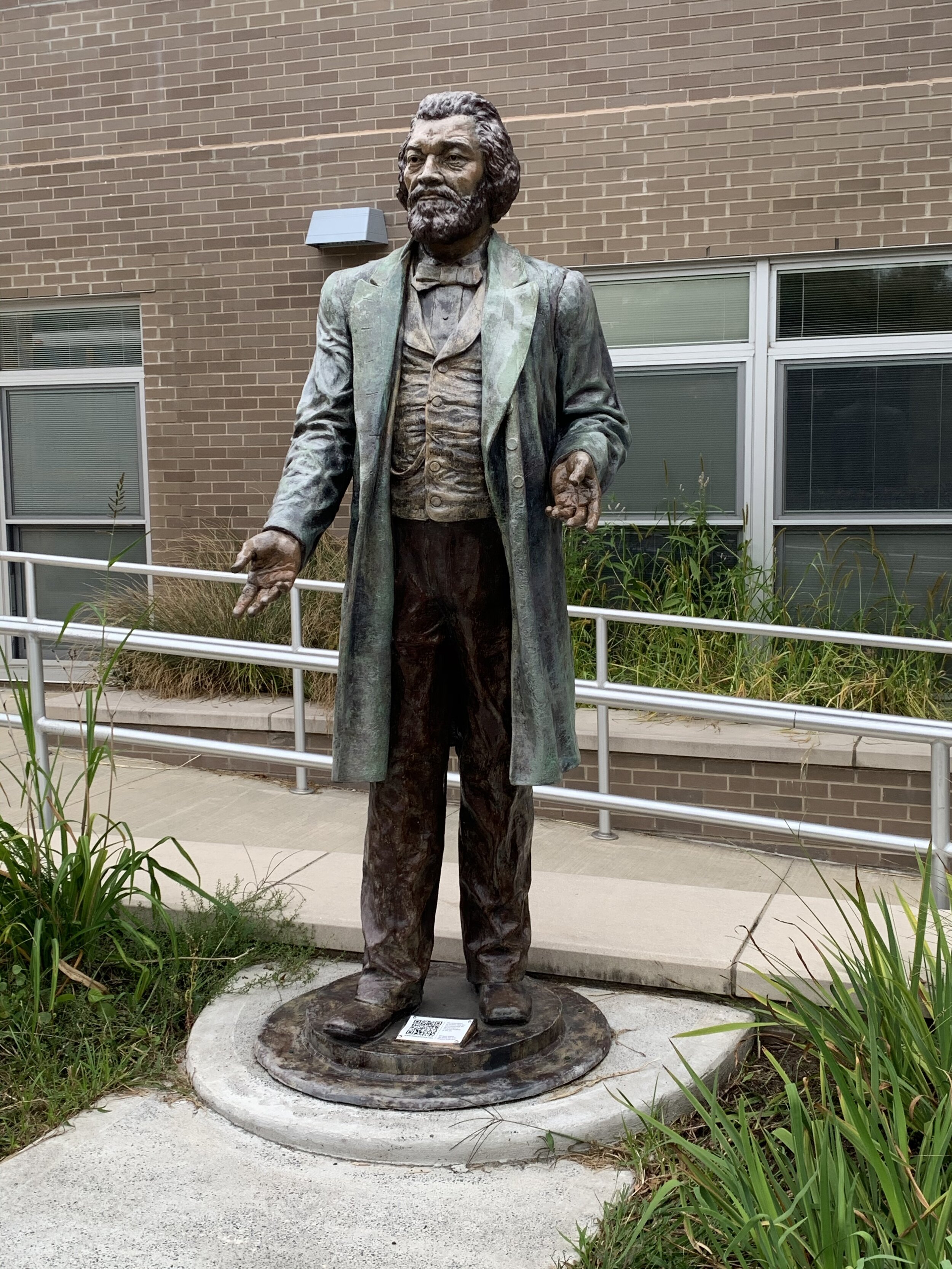

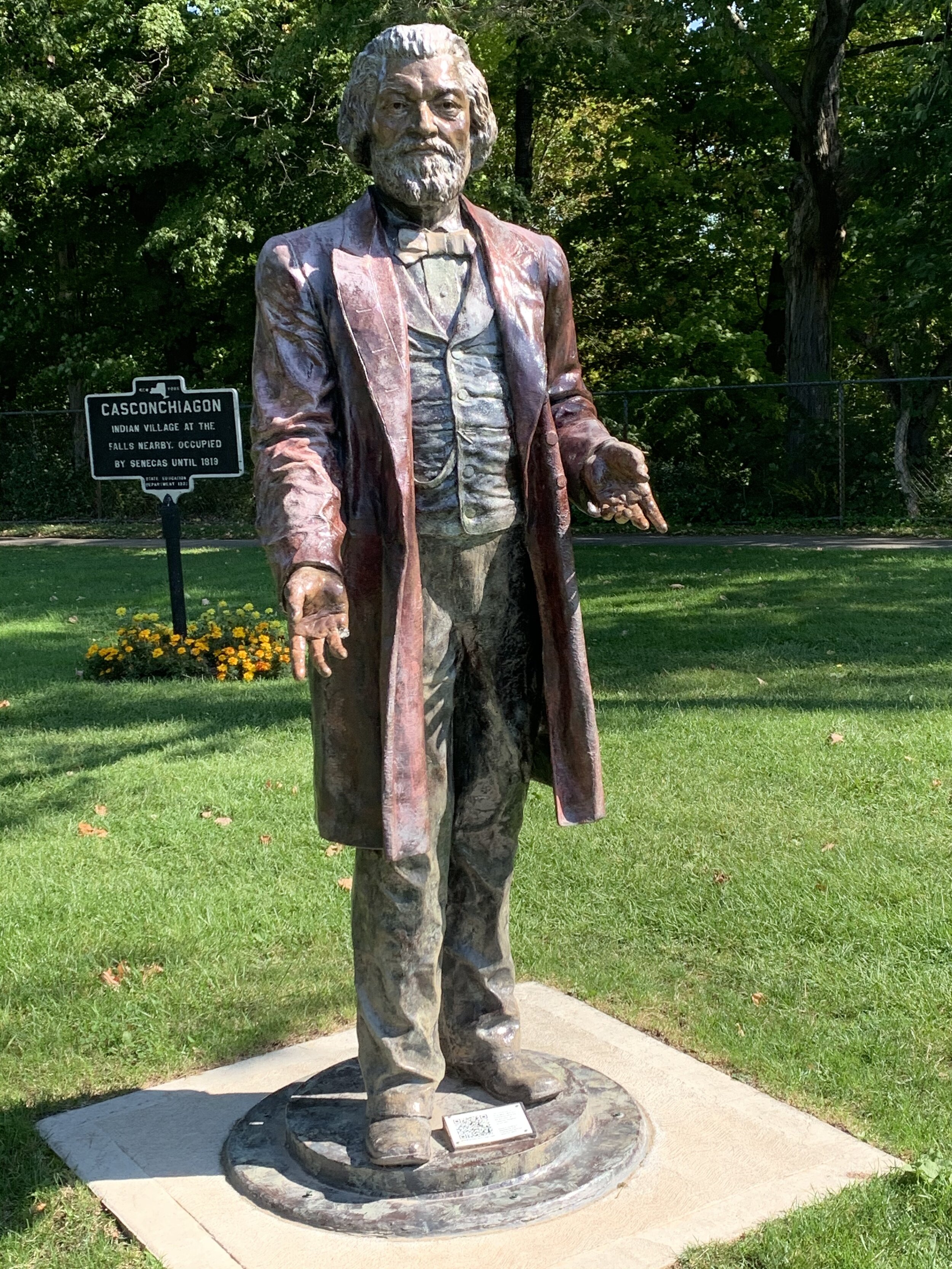

The Frederick Douglass Monument continues to have resonance for artists and communities in the twenty-first century. In 2018, the Rochester-based artist, Olivia Kim, reproduced Edwards’ statue in fiberglass. In honor of the 200th anniversary of Douglass’ birth (1818), thirteen of these statues were placed around the city at significant historic sites. Imagined through Re-Energizing the Legacy of Frederick Douglass project, the fiberglass statues are part of “a public art project, exhibition, and community-wide reflection commemorating” Douglass. I encountered four of the thirteen statues during my visit: one located at 999 South Avenue, the former site of the Douglass farm and Underground Railroad site, and now, outside the Anna Murray-Douglass Academy, School No. 12; one in the Mount Hope Cemetery, where Douglass is buried; one at the intersection of Corinthian and State Streets in downtown Rochester, where Douglass delivered his famed “What to a Slave is the Fourth of July” (July 5, 1852); and one at Kelsey’s Landing in Maplewood Park along the Genesee River, where Douglass fled Rochester by boat to Canada after John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry, West Virginia (October 1859).

Click on the image below to activate the slide show to see four of Olivia Kim’s fiberglass statues of Frederick Douglass.

I found the immediacy and “lightweight” nature of these reproductions at odds with the monumentality and gravitas of the Edwards bronze statue. This is not a bad thing, I think. Kim’s use of pigment, sometimes bright hues, brings the life-size scale of the fiberglass statues into our contemporary world.

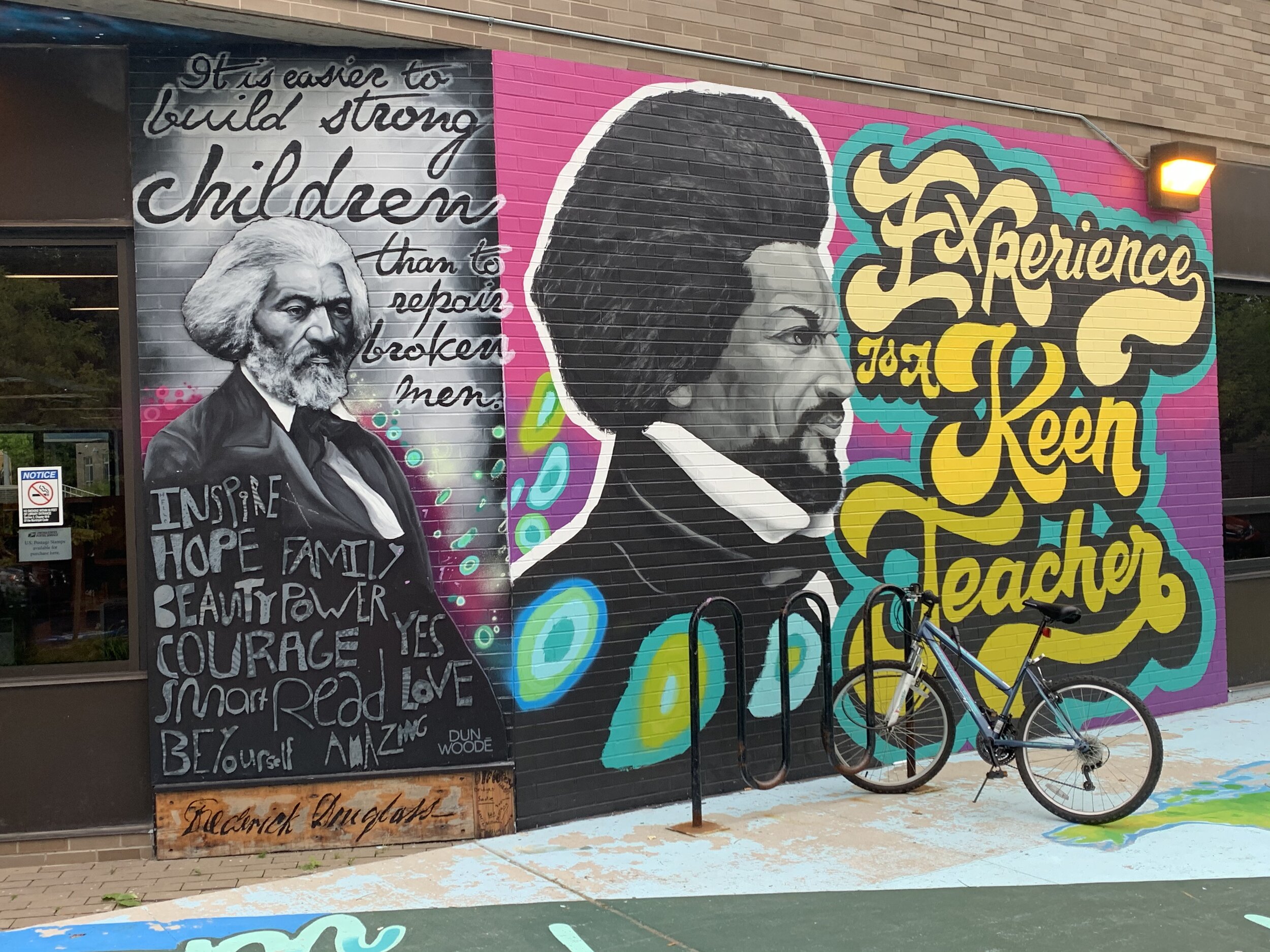

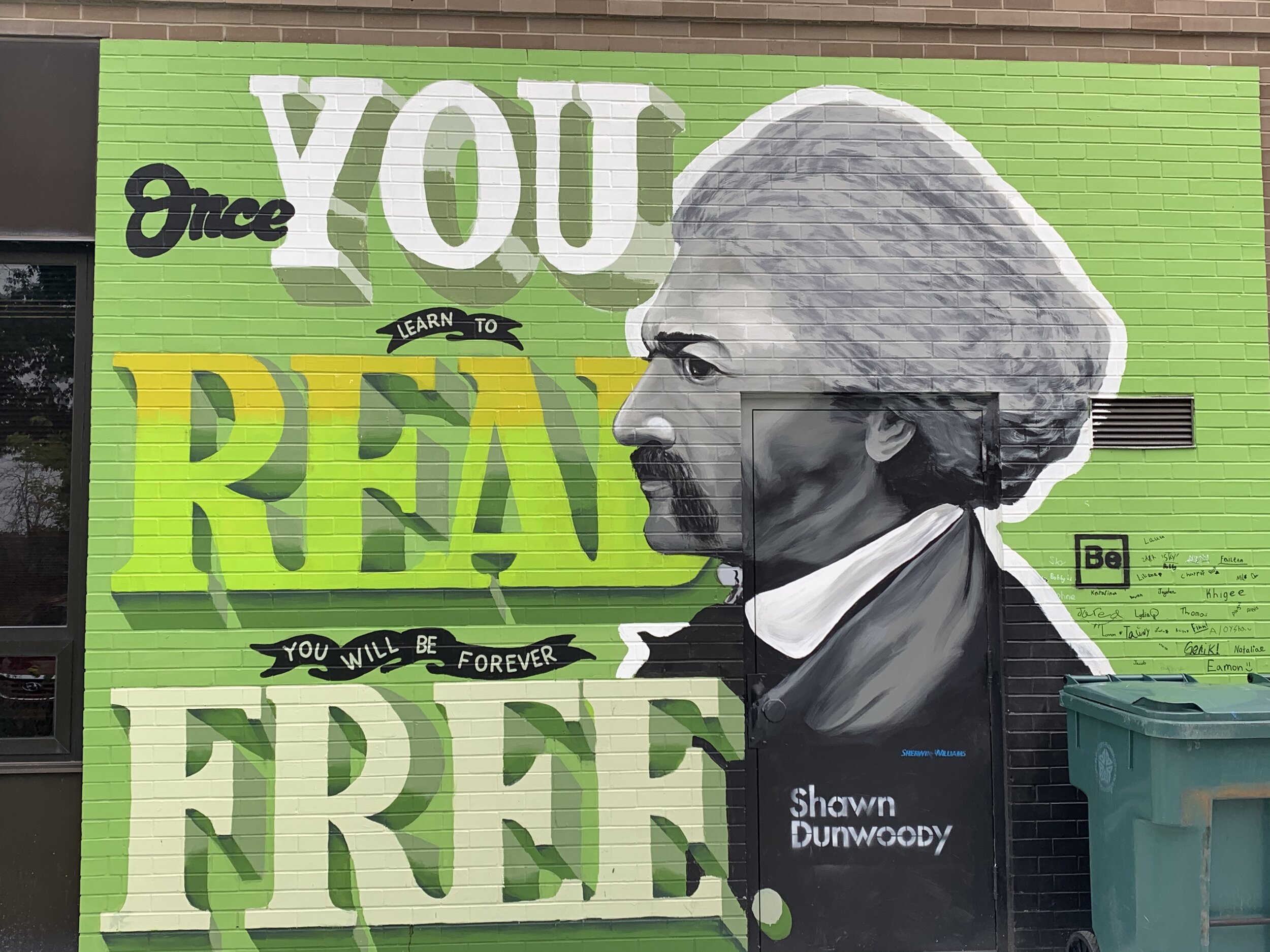

Murals at the School No. 12 and the Frederick Douglass Community Library, Rochester, New York. Photograph by Renée Ater, September 2019.

Along with the fiberglass statue of Frederick Douglass, another local artist, Shawn Dunwoody, created several community-sourced murals located on the walls of School No. 12 and the Frederick Douglass Community Library. These graphic images memorialize Douglass in a powerful visual manner with their bold use of color, design, and quotations. They function as day-to-day monuments to Douglass’ ideas for the students who attend School No. 12, for the community members who use the library, and for the citizens of Rochester.

Click on the image below to activate the slide show to see Shawn Dunwoody’s community-sourced murals at School No. 12.

Writing for WXXI News in June 2018, Tianna Manon details the scope of the community involvement in the mural project: “It’s not easy to bring together dozens of students, 100 cans of paint and a handful of artists to create a mural. But that’s exactly what community artist Shawn Dunwoody did this month. In honor of Frederick Douglass’ 200th birthday, Dunwoody, students and other artists and professionals came together to paint several wall-size murals at Rochester’s School 12, where Douglass’ home once sat. The murals depict portraits of Douglass alone and with other well-known historical figures such as Susan B. Anthony. Some of his quotes are also turned into art on the walls. . . . ‘Here at Frederick Douglass’ home, we worked with students to create this idea of home and we tell the story of the Underground Railroad,’ Dunwoody said.”