On June 27, 2020, I wrote a six-part post about the Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln in Washington, DC, on LinkedIn. A friend asked that I make it into a blog post. Here it is with revisions.

Thomas Ball, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (Emancipation Group), 1876. Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2009.

Thomas Ball's Freedmen's Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (1876) is a monument that I considered in my dissertation and wrote about in my book on Meta Warrick Fuller (chapter 3); one that I taught for twenty years; and most recently, one which begins a monument tour that I have given for two summers to a group of Fulbright Scholars on the problems of the memorial landscape in Washington, DC. I am well-versed in its history.

I view it as a complete failure of representation, rooted in nineteenth-century Neoclassical image-making based in racial type (that can be traced back to ancient examples); condescending gesture in the guise of equality; and a celebration of mythic republican ideals that were never upheld. This monument should be taken down. Its presence in 21st-century public space makes no sense. I am in agreement with Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton's call for the removal of the Freedmen's Memorial to Abraham Lincoln from Lincoln Park.

In his book, The Emancipation and the Freed in American Sculpture (1913), Freeman Henry Morris Murray asked a set of questions about race and public sculpture: "What does it mean? What does it suggest? What impressions is it likely to make on those who view it? What will be the effect on present-day problems, of its obvious and also of its insidious teachings?" These are fundamental questions we should ask of every monument.

Thomas Ball, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (Emancipation Group), 1876. Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2009.

Let's take a close look at the monument in relation to dress and gesture in order to understand why it is a problematic representation.

Ball’s composition includes two figures, one fully clothed, the other semi-nude. Due to the dozens of photographs that survive from the 1860s, we recognize that the standing bearded man is Abraham Lincoln. Dressed in a shirt with tie, a long coat, and trousers, Lincoln stands upright with most of his weight on one leg, in "contrapposto." Clothing and posture civilize Lincoln, marking his intelligence and morality.

The kneeling man, a newly emancipated enslaved person, is semi-nude. The only article of clothing that he wears is a piece of cloth draped from his waist to the edge of his buttocks. The sinewy muscles are clearly delineated in the man’s arms, legs, and abdominal muscles. Modeled with short curly hair, the former slave is also shown with a distinctive broad nose, signifying his African ancestry. We know from the historical record that former slave Archer Alexander was “the model” for the freedman. Yet, the portrait does not function as portraiture because it represents a racial type.

These attributes—nudity and the emphasis on his musculature and physiognomy—suggests “the savage,” a virulent image seen in a range of nineteenth-century visual culture. This difference between “the civilized man” and “the savage,” between Lincoln and the kneeling figure, is embedded in how we are meant to understand the image. This difference is the “insidious teaching.”

Gesture plays an important role as well in how we read the image. Lincoln’s right hand holds an unfurling scroll, the Emancipation Proclamation, which rests atop an octagonal-shaped plinth or short column. Lincoln’s left arm extends over the back of the kneeling man, his left index finger extending slightly upward. Ball modeled broken manacles on the kneeling man’s wrists; in his right fist, he grasps the links tightly, suggesting he has broken the bonds of slavery. Lincoln’s gesture is meant to show benevolence; the kneeling man’s gesture self emancipation. Instead, their gestures highlight a power differential—the might of the president as right and good, and the subservience of the kneeling figure as grateful and obsequious. Although the kneeling slave is supposed to have broken his own bonds, it is Lincoln who bestows freedom. The power relationship is one of a father and child, not an image of two men side-by-side in the quest for equality, freedom, and full citizenship.

Thomas Ball, Detail of Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (Emancipation Group), 1876. Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2009.

Thomas Ball, Detail of Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (Emancipation Group), 1876. Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2009.

The two architectural elements are also included and carry significant meaning. On the plinth/column is a profile portrait of George Washington. On either side of the portrait, Ball included fasces, a bundle of rods with an axe head, an ancient Roman symbol of judicial authority. In the context of the U.S. government, the fasces represents the power of the state over its citizens. Opposite the portrait of Washington is a modified shield with thirteen stars, representing the original thirteen colonies. Thirteen stars also adorn the base of the short column. I am reminded here that the colonies codified slavery into law and into American life.

Lincoln grasps the Emancipation Proclamation in his hand, resting it on top of a book and the column. Along the top of the column are stars representing the states in the Union in 1876. Ball used this imagery to make a direct connection between the republicanism of George Washington and that of Lincoln. Yet, in the present day, this imagery underscores the fact that George Washington was a slave owner and that the very fabric of the nation was interwoven with the subjugation and oppression of black people through the heinous system of slavery.

Thomas Ball, Detail of pillory from Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (Emancipation Group), 1876. Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2009.

The architectural element behind Lincoln and the newly emancipated man appears to be a wood stump. It is a post pillory that is roughly cut with a piece of cloth draped across its top. A vine of roses trails from the bottom of the pillory to mid-way up, interlacing into the ring attached to it. A ball and chain rests at the base of the torture device. Here Ball attempted to signal that slavery and the use of pillory had come to an end—the climbing vine can be read as representing strength and determination.

Murray would implore us to ask what exactly does this image mean in the twenty-first century. In 1913, he wrote that monuments are not static objects whose meanings remain the same through time. Although we may believe that a monument’s meaning is fixed in space and time, this simply is not true. We must constantly ask what is the monument saying and doing in the present. This monument, with an additional cast in Boston, uses archetypal imagery of the slave, a black man stripped of clothing, and whose self-emancipatory gesture is subsumed by his kneeling pose and the towering figure of a benevolent Lincoln.

Robert Berks, Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial, 1974. Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2009.

It’s present-day location is also key to how we understand Freedmen's Memorial to Abraham Lincoln. The monument resides in Lincoln Park with the Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial. Installed at the east end of the park in 1974, the Bethune Memorial celebrates the noted educator and civil rights activist. Its exuberant modern form further undermines the currency of the Ball monument.

This is a well-used public space. At the east end of the park, two children's playgrounds frame the Bethune Memorial. On any given day, you can hear the excited play of children. What does it mean that each and every day that children enter this park, they must encounter an anachronistic monument of a kneeling black man in supplication to the heroic, fully dressed Abraham Lincoln? I would not want my grandson—a beautiful, happy little boy with an engaging smile—to encounter such a monument that emphasizes inequality and stereotype.

It is not enough to argue that free blacks and formerly enslaved paid for the monument. It is not enough to argue that Archer Alexander's image is the model for the kneeling figure. It is not enough to argue that Frederick Douglass delivered the dedicatory speech and recognized the role of Lincoln in black freedom. It is not enough to argue that racist imagery has a lesson to teach us now. It is not enough to simply reinterpret for a 21st-century public. We understand what we see. Freedmen’s Memorial should not remain in this space.

Ed Hamilton, Spirit of Freedom, African American Civil War Monument, 1998. Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2012.

I can think of one monument in Washington, DC, that celebrates empowered black men, responsible for fighting for their freedom. As I have written elsewhere, Ed Hamilton's Spirit of Freedom and the African American Civil War Monument directly challenge the visual vocabulary of the Ball monument and the notion of what black emancipation and freedom can look like. Sited at Vermont Avenue and U and 10 Streets, NW, this monument dedicated to the United States Colored Troops asks us to reconsider the role of black men and black families in their own self-emancipation. It's a strong visual statement, handled with care and deep consideration. These are men consciously fighting to be free of slavery, standing erect, fully clothed, caught in the surge to battle. It recognizes a multi-generational family on the back of the monument, in its concave form, who also stand for freedom. Unfortunately, it is also a monument that many visitors to the city never see because of its location outside the monumental core of Washington, DC. What would it look like to re-envision the monumental core of Washington to include the story of slavery, emancipation, and freedom?

Ed Hamilton, Spirit of Freedom 1998. Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2012.

Ed Hamilton, Spirit of Freedom 1998. Washington, DC. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2012.

POSTSCRIPT: Last October, I gave a lecture for the Friends of the Boston Public Garden, focusing on monuments to United States Colored Troops. Before the talk, I walked around the neighborhood of my hotel and came upon a second cast of Thomas Ball’s Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln. The inscription on its based points to the problems I have outlined above: “A Race Set Free and the Country at Peace, Lincoln, Rests from his Labors.” I was struck anew that the monument is misplaced in time. During the question and answer period, I argued that such imagery has no place in public space today and lacked significant meaning in the 21st century. To my surprise, I learned today that the Boston Art Commission voted unanimously to remove the city’s cast of the Ball monument from public view.

Thomas Ball, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln (Emancipation Group), 1879. Park Square, Boston, Massachusetts. Photograph by Renée Ater, 2019.

For those interested in a full narration of the commission and creation of the monument, see Kirk Savage, Standing Soldiers, Kneeling Slaves: Race, War, and Monument in Nineteenth-Century America, new edition (1997; Princeton University Press, 2018).

UPDATE: July 4, 2020

Today, the Wall Street Journal ran a story about the discovery of Frederick Douglass response to Thomas Ball’s Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln. On April 19, 1876, Douglass wrote in part: “The negro here, though rising, is still on his knees and nude. What I want to see before I die is a monument representing the negro, not couchant on his knees like a four-footed animal, but erect on his feet like a man.” Historian Scott Sandage uncovered Frederick Douglass’ letter to the editor of the National Republican:

Frederick Douglass, “A Suggestion: To the Editor of the National Republican,” National Republican, April 19, 1876. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/resource/sn86053573/1876-04-19/ed-1/?sp=4&r=0.073,1.119,0.367,0.186,0

Ted Mann, “How a Lincoln-Douglass Debate Led to a Historic Discovery,” Wall Street Journal, July 4, 2020, https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-a-lincoln-douglass-debate-led-to-historic-discovery-11593869400. For the full story, see Jonathan W. White and Scott Sandage, “What Frederick Douglas Had to Say About Monuments,” Smithsonian Magazine, June 30, 2020, https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/what-frederick-douglass-had-say-about-monuments-180975225/.

Bullard & Bullard, National Emancipation Monument, 1889. Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003670712/.

UPDATE: July 6, 2020

Read Elizabeth R. Varon’s excellent “The Statue That Never Was,” on the Blog of the John L. Nau III Center for Civil War History, University of Virginia, July 6, 2020, https://naucenter.as.virginia.edu/blog-page/1231.

Varon explores the fascinating story of the National Emancipation Monument, conceived but never built. She writes: “In this monument—which lived a brief evocative life in words and images, though it never took the form of granite and bronze—a black Civil War officer, André Cailloux, stood at the apex with white politicians arrayed at the base. The story of this project, and of its principal champion George W. Bryant, challenges us to reimagine how we remember and represent the Civil War.”

UPDATE: July 10, 2020

“Over the past few weeks, there has been extensive debate across the U.S. about statues depicting the Confederacy and other troubled aspects of American history. In the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Washington, D.C., the Emancipation Memorial – also known as the Freedman’s Memorial -- is one such symbol. Jeffrey Brown talks to four Black Americans to gauge differing views on the structure.”

PBS NewsHour, “These Black Americans See a Statue Memorializing Lincoln in Different Ways,” July 10, 2020, https://www.pbs.org/newshour/show/how-black-americans-see-a-statue-memorializing-lincoln-in-different-ways.

UPDATE: September 8, 2021

Thomas Ball, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln, 1876, Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photo by Nicole Peppe, September 8, 2021

Robert Berks, Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial, 1974, Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photo by Nicole Peppe, September 8, 2021

On September 8, 2021, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln and the Mary McLeod Bethune Memorial were vandalized. On the base of the Bethune memorial, the vandal wrote “Lincoln Did Not Free The Slaves.” Unfortunately, the person(s) seemed to not know the importance of Bethune’s work as an educator and founder of the National Council of Negro Women. The National Park Service showed up quickly to power wash the paint from the monuments.

Thomas Ball, Freedmen’s Memorial to Abraham Lincoln, 1876, Lincoln Park, Washington, DC. Photo by Nicole Peppe, September 8, 2021.

This cardboard sign was left at the base of the memorial on September 8 as well. The cardboard sign reads: “Admirable as is the monument by Mr. Ball in Lincoln’s Park, it does not, as it seems to me, tell the whole truth . . . there is room in Lincoln Park for another monument. —Frederick Douglass, 1876”, #morehistory2021

UPDATE: January 15, 2022

Thomas Ball (1819 - 1911), Emancipation Group, 1865. Bronze. 33 in. x 24 in. x 16 in. (83.82 cm x 60.96 cm x 40.64 cm). The Lunder Collection, Colby Museum of Art, Colby College, Watertown, Maine

In October 2021, I had the pleasure of visiting Professor Tanya Sheehan’s class at Colby College. For their final paper assignment, the students in her class, Slavery and Freedom in American Art, engaged and critically reframed the Emancipation Group in the Colby Museum of Art. We had a great session in the museum looking at and discussing the work. This small cast/iteration departs iconographically from the monument in Washington, DC. In this version, we see the image of the enslaved man, still kneeling with broken manacles on his wrist, but wearing a Phrygian or liberty cap. Lincoln still stands above the Black figure, but no longer holds the unfurled Emancipation Proclamation. Instead, Lincoln’s hand rests on a shield atop a stack of four large books. Inscribed on the base, unlike the monument in Lincoln Park, are the words: “And upon this act—I invoke the considerate judgment of mankind and the gracious favour of Almighty God.”

Numerous small versions of the Emancipation Group exists in bronze and marble with slightly different use of symbolic imagery. Below is an example from the Chazen Museum of Art (formerly the Elvehjem Museum of Art) at the University of Wisconsin, Madison, which more directly references the 1876 monument.

Thomas Ball, Emancipation Group, 1873, marble. Chazen Museum of Art (formerly the Elvehjem Museum of Art), University of Wisconsin, Madison, Wisconsin

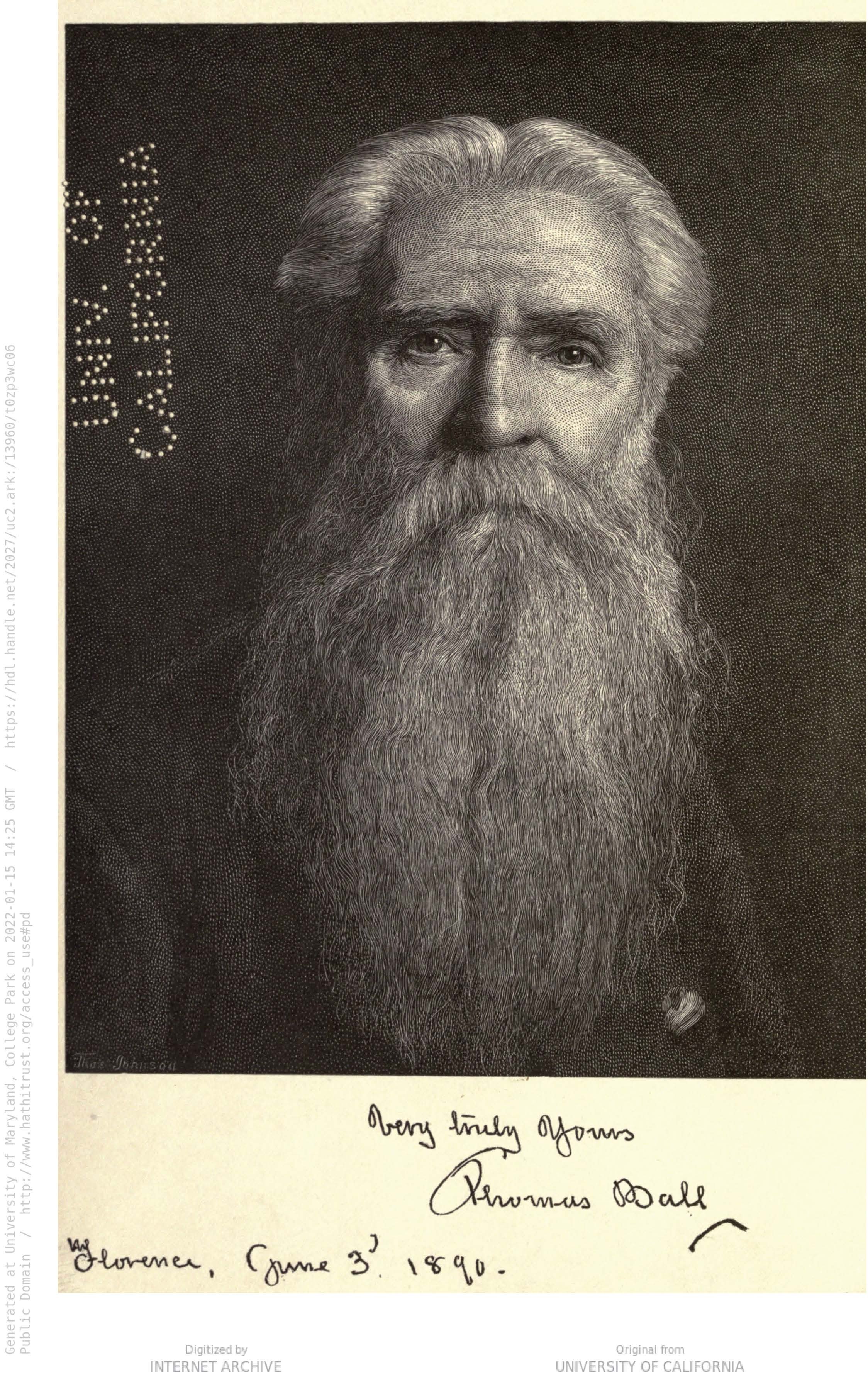

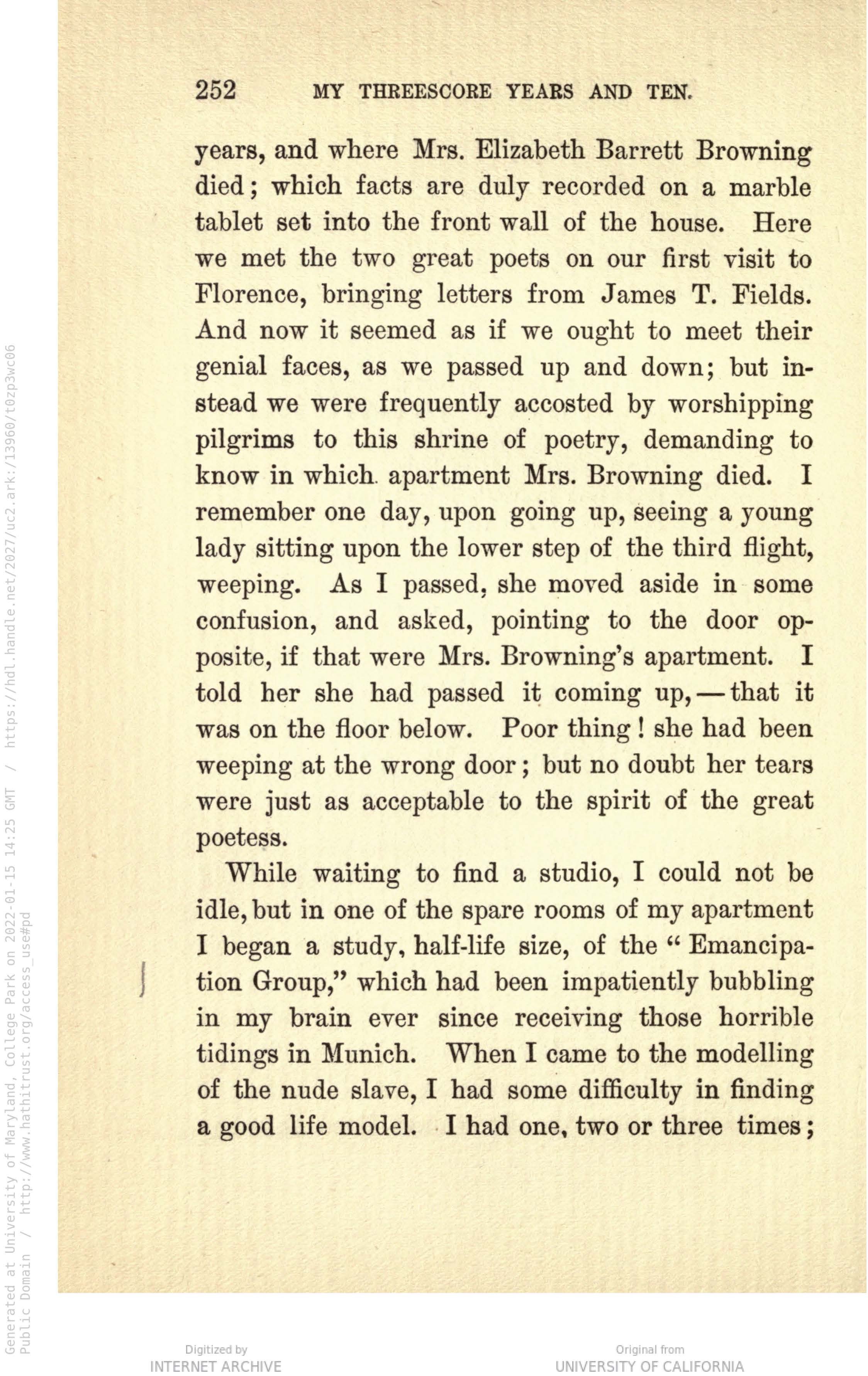

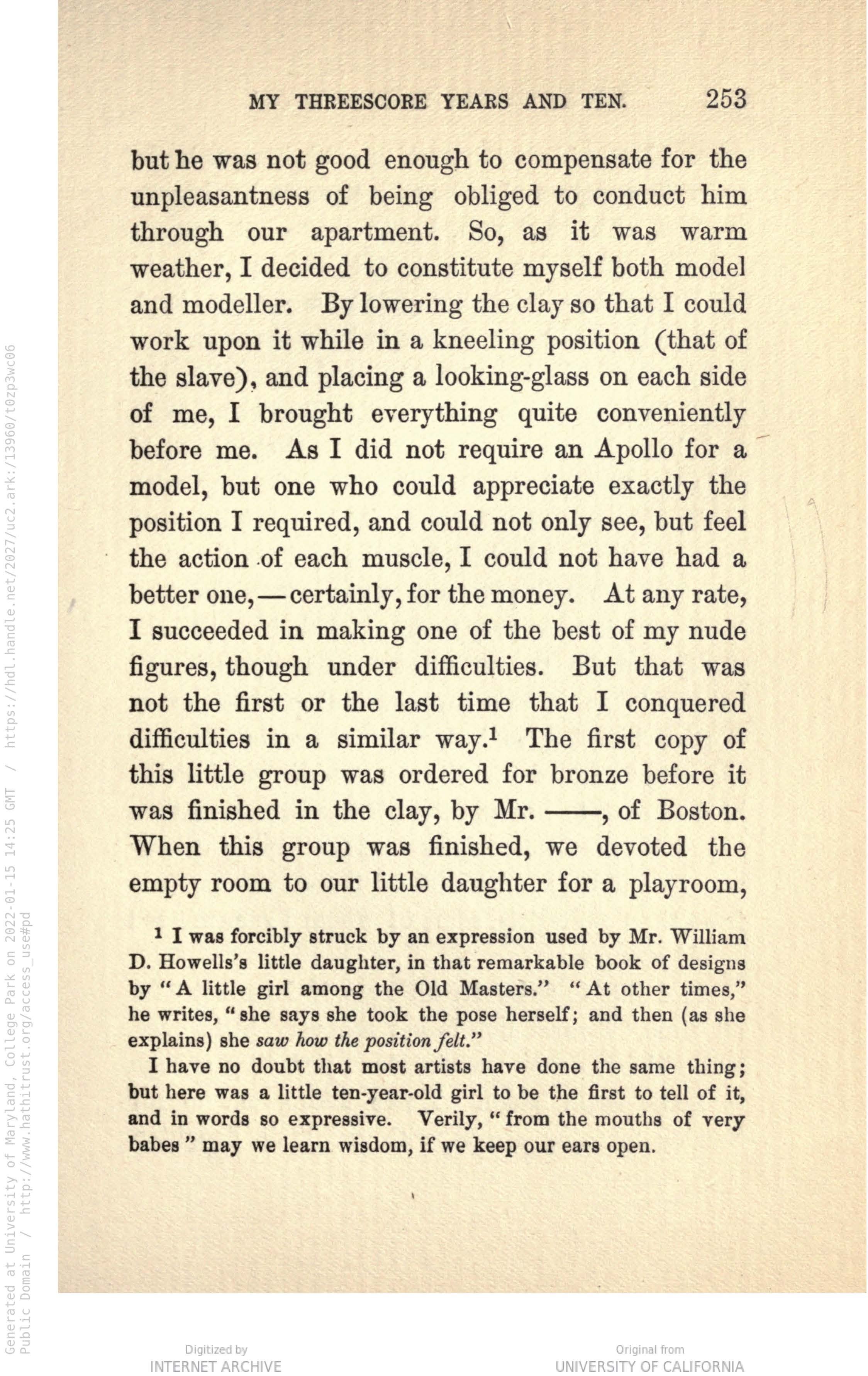

One of the most interesting things to come out of this visit was Professor Sheehan’s pointing to Ball’s writing on the sculpture. In his autobiography, My Threescore Years and Ten, Ball wrote that he used himself as the model for the “nude slave”!

“While waiting to find a studio (in Florence), I could not be idle, but in one of the spare rooms in my apartment I began a study, half-life size, of the “Emancipation Group,” which had been impatiently bubbling in my brain ever since the horrible tidings in Munich (news of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865). When I came to the modeling of the nude slave, I had some difficulty in finding a good life model. I had one, two or three times; but he was not good enough to compensate for the unpleasantness of being obliged to conduct him through our apartment. So, as it was warm weather, I decided to constitute myself both model and modeller. By lowering the clay so that I could work upon it while in a kneeling position (that of the slave) and placing a looking-glass on each side of me, I brought everything quite conveniently before me. As I did not require an Apollo for a model, but one who could appreciate exactly the position I required, and could not only see, but feel the action of each muscle, I could not have had a better one,—certainly for the money. At any rate, I succeeded in making one of the best of my nude figures, though under difficulties.”

—Thomas Ball, My Threescore Years and Ten: An Autobiography

Ball’s writings reveal several things. First, Ball conceived of the ‘Emancipation Group’ in response to the news of Abraham Lincoln’s assassination in April 1865. Second, after settling in Florence, Italy, in the same month, he purported to have difficulties finding a good life model, so he used his own physiognomy and body as the model for the “slave.” Third, he writes that the model “was not good enough to compensate for the unpleasantness of being obliged to conduct him through our apartment.” This comment suggests Ball’s own biases regarding working class models in Florence, perhaps one needed to be beautiful in order to enter the sanctity of his home.