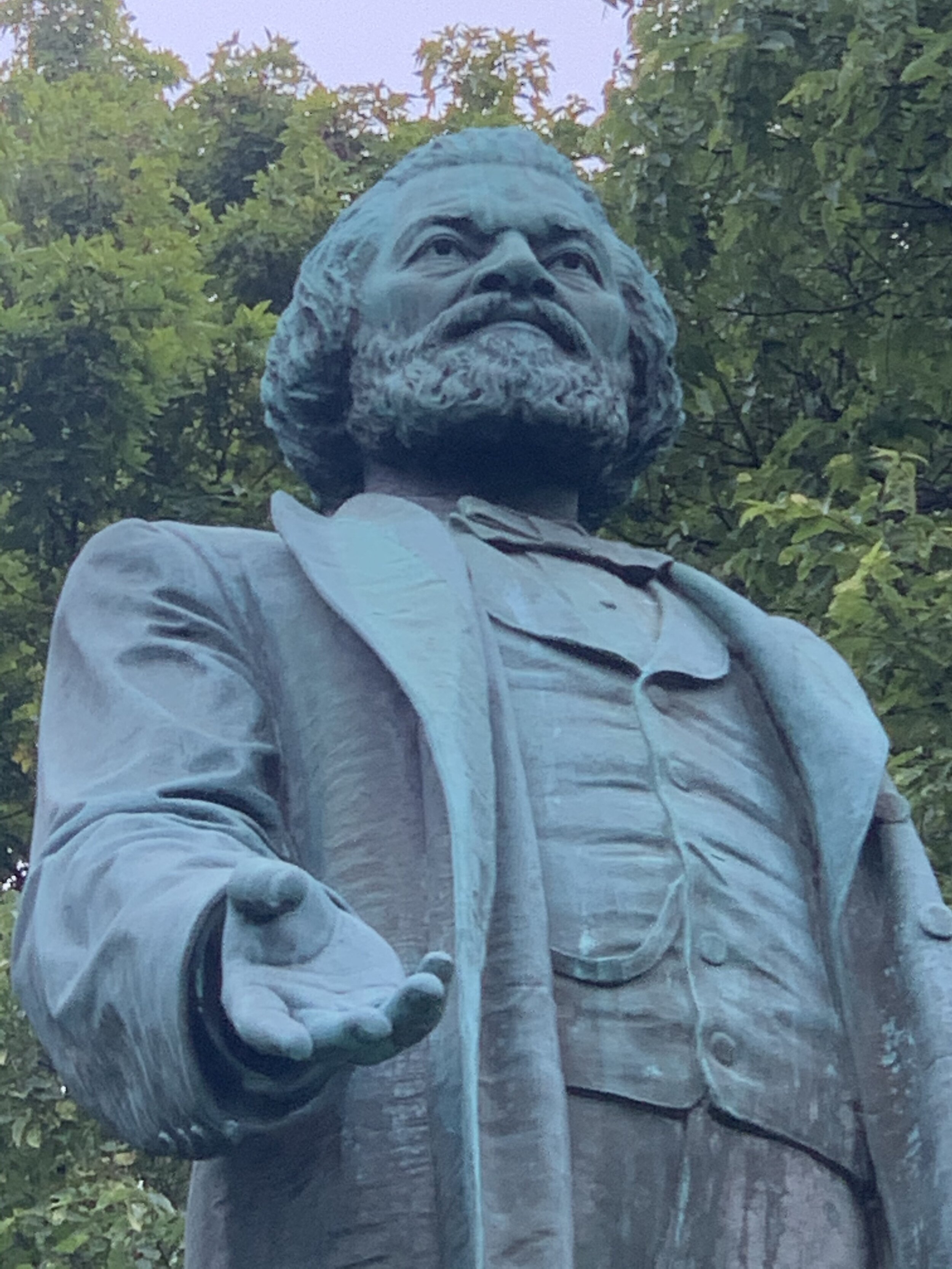

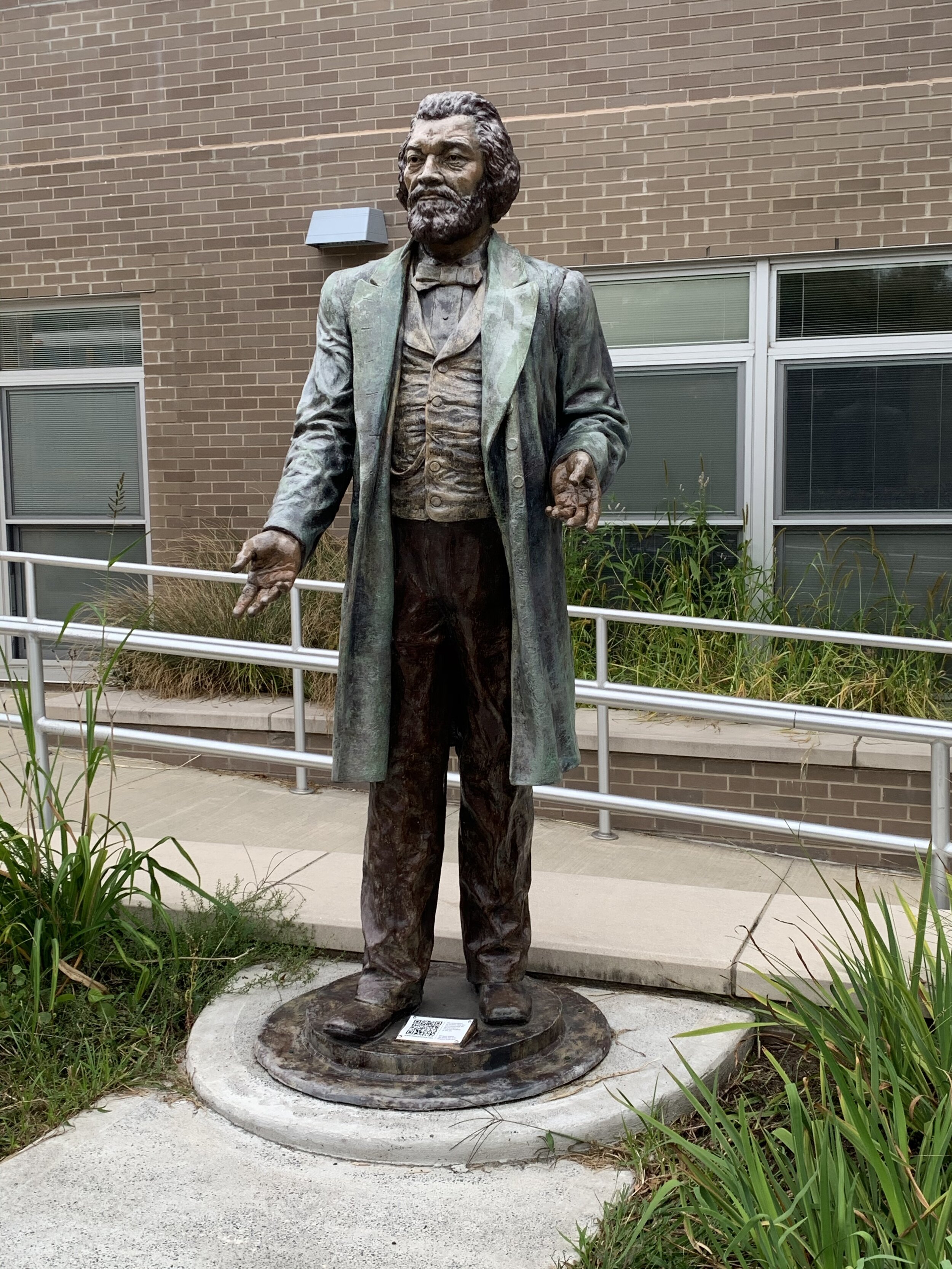

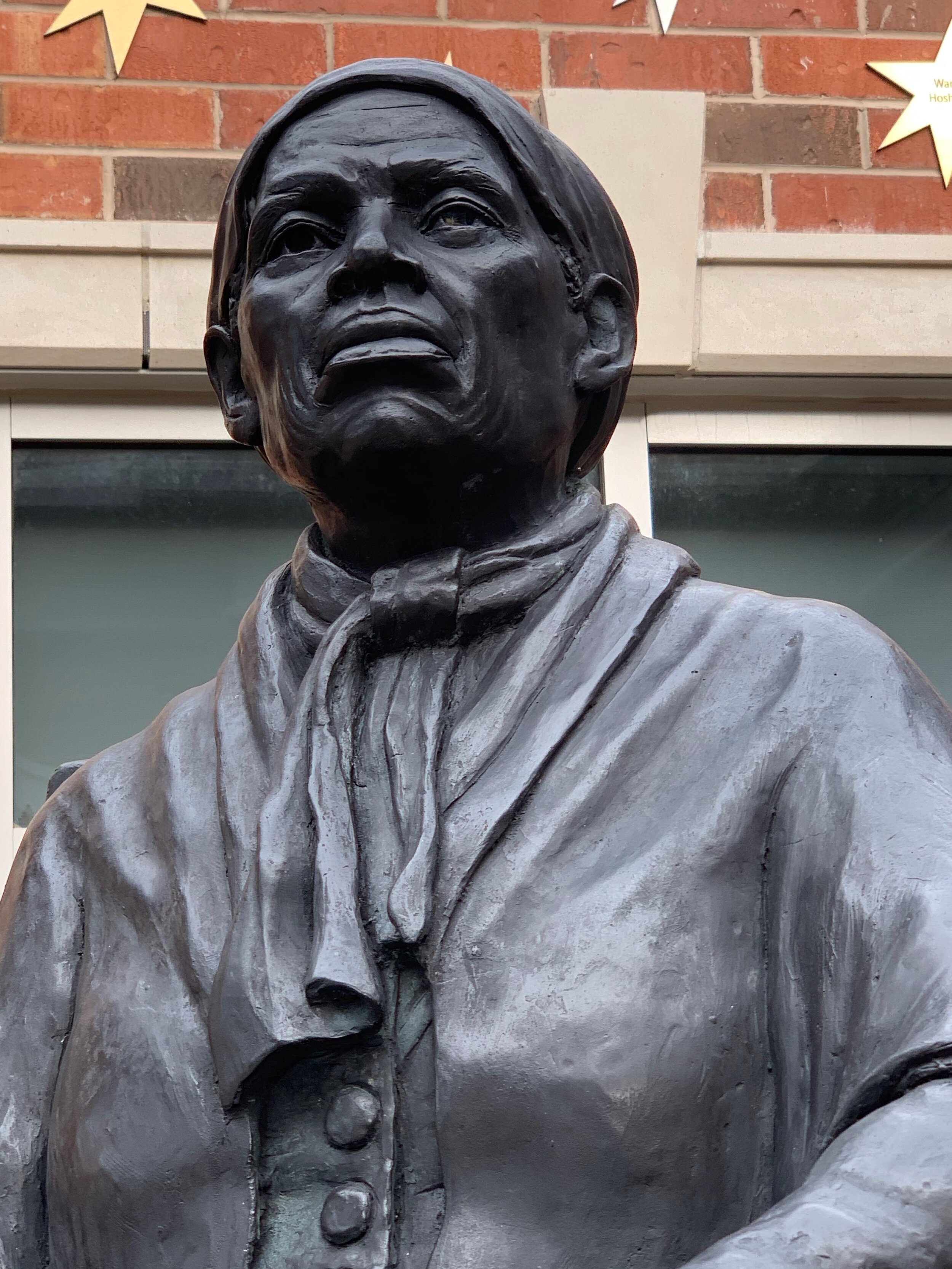

Let's take a close look at the monument in relation to dress and gesture in order to understand why it is a problematic representation.

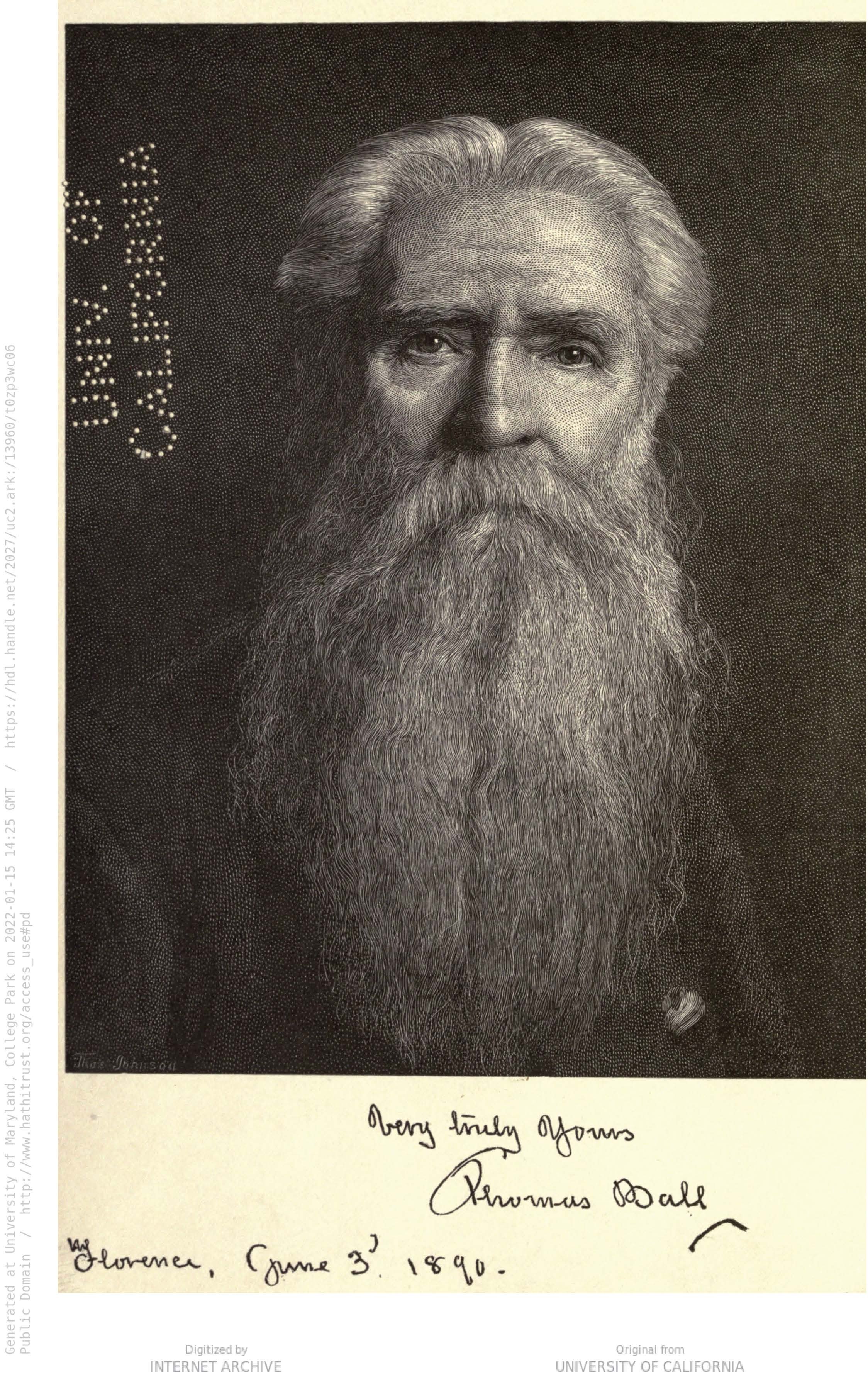

Ball’s composition includes two figures, one fully clothed, the other semi-nude. Due to the dozens of photographs that survive from the 1860s, we recognize that the standing bearded man is Abraham Lincoln. Dressed in a shirt with tie, a long coat, and trousers, Lincoln stands upright with most of his weight on one leg, in "contrapposto." Clothing and posture civilize Lincoln, marking his intelligence and morality.

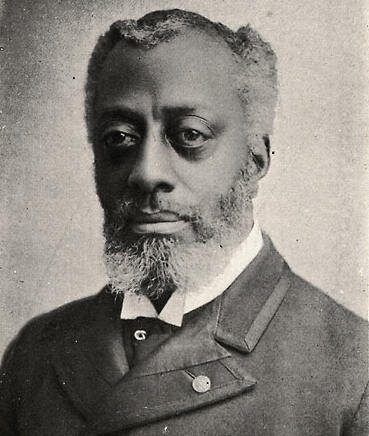

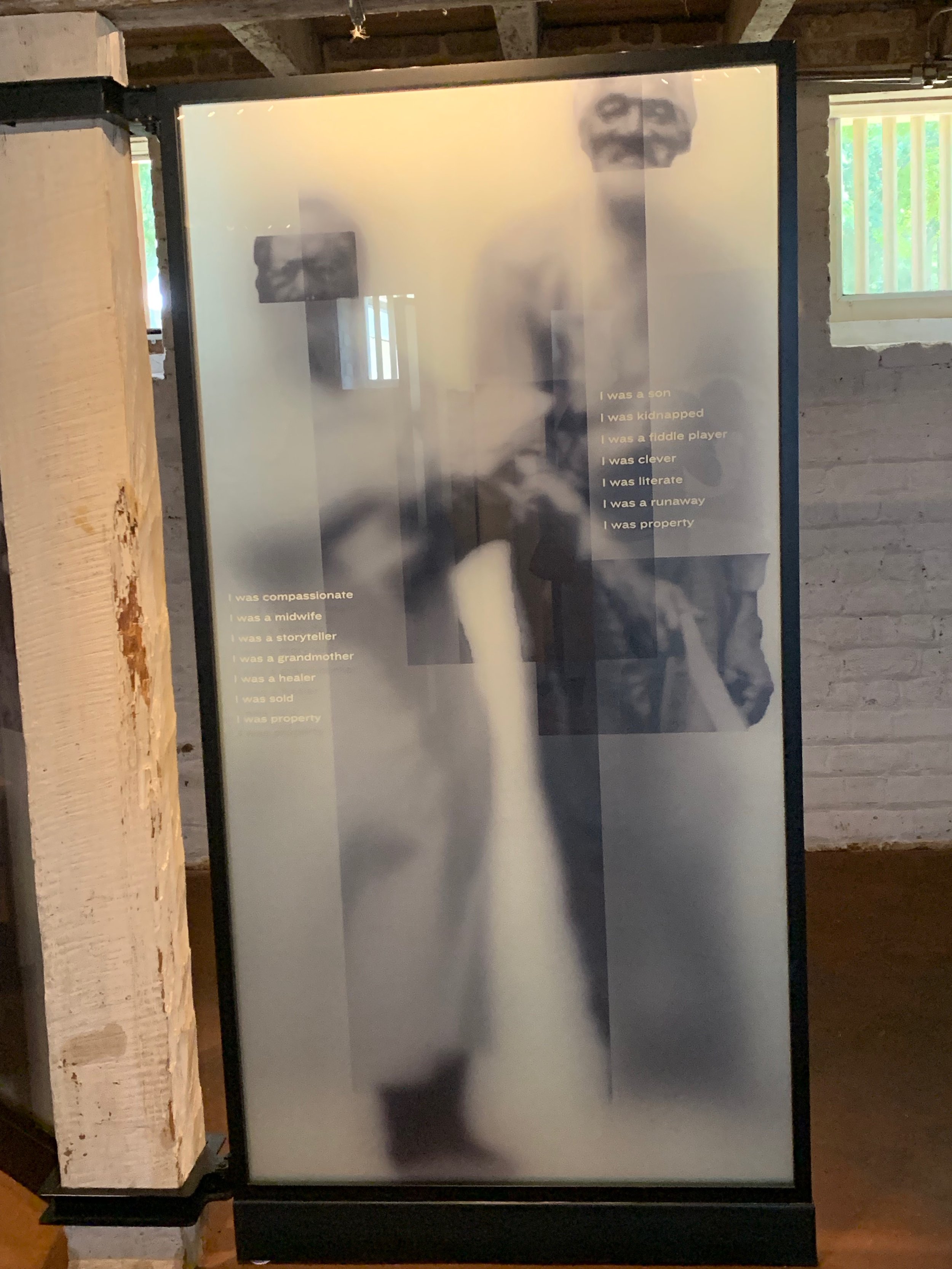

The kneeling man, a newly emancipated enslaved person, is semi-nude. The only article of clothing that he wears is a piece of cloth draped from his waist to the edge of his buttocks. The sinewy muscles are clearly delineated in the man’s arms, legs, and abdominal muscles. Modeled with short curly hair, the former slave is also shown with a distinctive broad nose, signifying his African ancestry. We know from the historical record that former slave Archer Alexander was “the model” for the freedman. Yet, the portrait does not function as portraiture because it represents a racial type.

These attributes—nudity and the emphasis on his musculature and physiognomy—suggests “the savage,” a virulent image seen in a range of nineteenth-century visual culture. This difference between “the civilized man” and “the savage,” between Lincoln and the kneeling figure, is embedded in how we are meant to understand the image. This difference is the “insidious teaching.”

Gesture plays an important role as well in how we read the image. Lincoln’s right hand holds an unfurling scroll, the Emancipation Proclamation, which rests atop an octagonal-shaped plinth or short column. Lincoln’s left arm extends over the back of the kneeling man, his left index finger extending slightly upward. Ball modeled broken manacles on the kneeling man’s wrists; in his right fist, he grasps the links tightly, suggesting he has broken the bonds of slavery. Lincoln’s gesture is meant to show benevolence; the kneeling man’s gesture self emancipation. Instead, their gestures highlight a power differential—the might of the president as right and good, and the subservience of the kneeling figure as grateful and obsequious. Although the kneeling slave is supposed to have broken his own bonds, it is Lincoln who bestows freedom. The power relationship is one of a father and child, not an image of two men side-by-side in the quest for equality, freedom, and full citizenship.